I drove towards the stadium wearing my Sunday Best (#55) with two Jets fans, a Bears transplant and a Redskins supporter.

“Are the Ravens playing at home this week? Maybe we should just go to a bar and avoid the stadium traffic.” My passenger had never been to Baltimore. “Yes,” I responded, “they are playing at home today. That’s the whole point.” We didn’t have tickets to the game, but RavensWalk on a Sunday is to me, pure magic. There’s an energy to the masses. If you’ve never been, even if football is a sport you could care less about, you should go, because the implications of a stadium in a city are far greater than what goes on inside.

As we walked through the Camden Yards gates, the skeptical visitor broke away to stare at the deserted green diamond. “I’ve never been in the gates before. Can we stay here a minute?”

Home: 1

Skeptical Visitor: 0

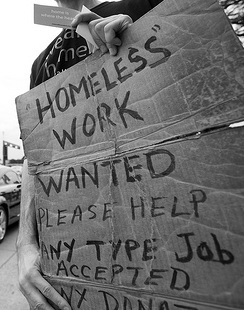

Logistically, the urban stadium is a tricky feat to execute. By definition, urban areas are dense and restricted. By implication, stadiums are seasonal magnets for crowds, traffic, informal economies and overpriced team paraphernalia. The promise of economic development is a tried and true argument for stadium construction – after all, city councils and economic development corporations smile broadly upon the promise of increased revenue through sports. Though along with the promise of these benjamins comes the hope of the Ripkens, the Ray Lewises, and the unifying act of someone in the Ritz putting on the same jersey as a renter in O’Donnell Heights. Urban stadiums, accessible patronage, and hometown heroes with whom we identify transcend demographics and poverty lines. When it comes to sports, city fans band together, regardless of the social elements which usually split us apart.

In Baltimore we have two world class models of the urban stadium. They’ve been built to fit the existing city fabric, to manage gameday crowds through strategically placed traffic patterns, parking lots, and public transit, and are pedestrian oriented. Anyone in the city can get within one hundred feet of the action, but economic access to get into the game still remains unbalanced. In essence, nearly anyone with a disposable ten-dollar bill can spend a summer evening at the Yard, but at the time of publication, a ticket to the Ravens game started at $70 on stub hub.

Despite the price tags, the unifying presence of a sports team trumps the inequality of access to the game. Sports, particularly in Baltimore, create solidarity in a city quite often divided. East side v. Westside, uptown v. downtown, we all come together under the devise of a color or a mascot. Collectively we have a common opponent and a common objective – Beat the _________. Placement of a stadium within the city proper gives otherwise socially marginalized communities access to resources encouraging this solidarity. This begs the question, why don’t cities do more to encourage collective access through building projects? Should we continue to build the Patterson Parks when the average user is unlikely to spend $12 on a cheesesteak at the bordering bistro? The presence of this community space should be enough to discourage the transition from green space to parking lot.

The first hindrance is practical; cities are tightly confined. A large inclusionary project like an urban stadium demands land that spans blocks dedicated to parking, in addition to space for the stadium itself. The second hindrance is less tangible; what good is city pride and can it be quantified? When a project is brought before city council, directly resulting dollar figures are the key for approval. The promise of city pride and cheering residents often do little by way of convincing evidence. Yes, city pride may increase homeownership and permanence. Perhaps people who love their cities are less likely to move away, a desirable characteristic for a city with constant population decline. The greater question remains disposable income – where the element of pride loses its conviction in a forum where money speaks loudly.

I argue we should continue to bring people together and bridge the gap between local poverty and wealth despite the divide in spending power. When we get a touchdown, I hi-five the man next to me just as quickly as I hide behind a stranger when a pop fly heads my way. The stadiums in Baltimore have made sports accessible. We can see them, smell them, be part of them. The presence of these franchises in my backyard makes me feel part of something greater. It’s nice that for those few moments, during gametime, socioeconomic divides are blanketed by purple, orange, or Tar Heel blue. If we’re not at the game, we’re at a corner bar – all on the same playing field.