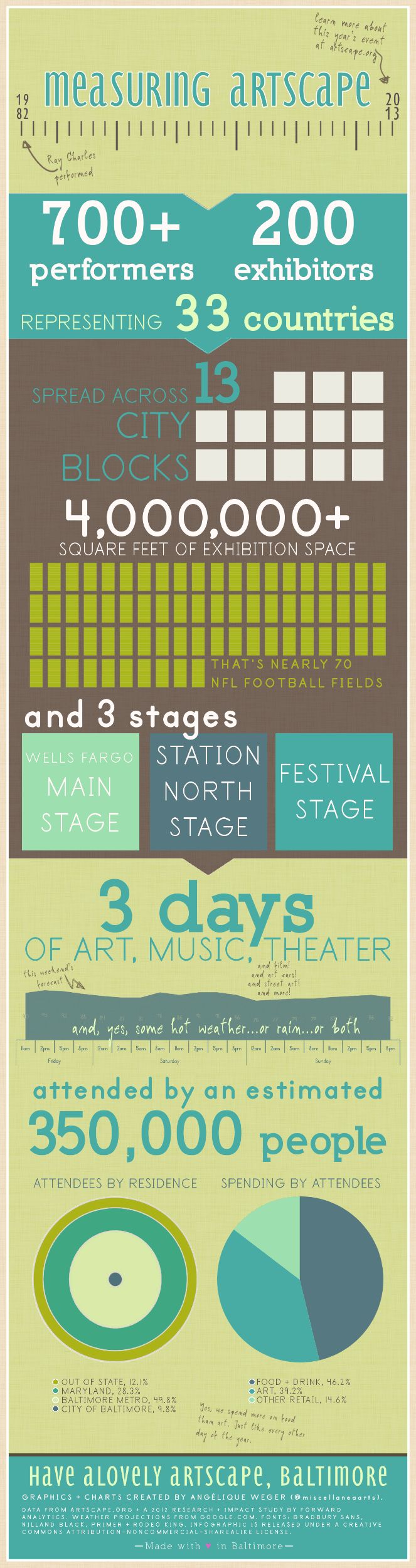

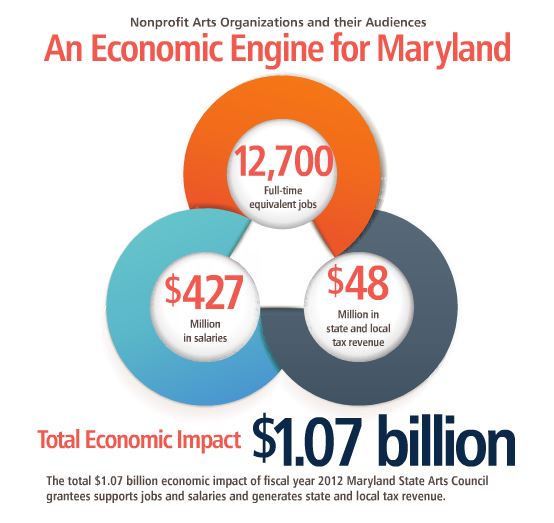

The Economic Impact of the Arts in Maryland: FY2012 report by the Maryland State Arts Council

In a single visual, this is pretty much everything that’s wrong to me about how we talk about about the impact of art and arts organizations. Granted, I myself have highlighted efforts that quantify the impact of art in this way, mainly because it so dominates the research of what makes art powerful and, in the eyes of funders, worthy.

But I’ve also written a lot in this space about finding a better way.

Economic impact is pretty low-hanging fruit in terms of data related to arts and impact. Money and jobs are easily quantifiable and pretty clearly Good Things the arts should line up to take credit for. But is it why we make art? Why we subscribe to theater seasons, attend art museums or listen to music? As Ben Cameron of the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation asks in the foreward to Counting New Beans: Intrinsic Impact and the Value of Art:

…do artists really create work to leverage additional dollars for the local economy? Do audiences really go to the theater to drive local SAT scores higher?

It’s obvious that we do not, and reports like Counting New Beans do the hard work of establishing why people seek out arts experiences and what they gain by doing so. The study summarized in Counting New Beans looked at 18 theaters in 6 regions and, instead of focusing on their work’s extrinsic values—like the economic indicators above—established categories of intrinsic value and researched those.

This distinction between extrinsic and intrinsic isn’t new; Gifts of the Muse (PDF full report) attempted to provide what Ian David Moss calls a “grand unifying theory” of the benefit of arts back in 2004, exploring instrumental/extrinsic and intrinsic benefits as they had been discussed and researched to date. The research outlined in Counting New Beans builds upon this, quantifying audience experience in areas like:

- Anticipation (“How much were you looking forward to this performance?”)

- Captivation (“How absorbed were you…?”)

- Post-performance Engagement (“Did you leave the performance with questions you would have liked to have asked the actors, director or playwright?”)

These are intrinsic values, the transformative emotional, social and intellectual experiences that result when we view art. They’re hard to get at and quantify because audience members aren’t always able to articulate their experience (i.e., great art may render someone speechless, which is an amazing feat as an artist and a contraindicated one as a researcher).

These values can be difficult to summarize in a single measure of impact, unlike the dollar signs above. Some works are connected to emotionally vs. intellectually, some works are calls to action, others result in a sense of familiarity or connection. As a result, some of the survey tools used produce both qualitative data about how audience members were impacted (e.g., “How did you feel after this performance?”) and quantitative data about the degree of impact ( e.g., weighing the emotional impact of a performance on a scale of 1-5). The resulting qualitative data lets arts organizations know if the audience left feeling sad or hopeful, while the quantitative data establishes how deeply the work made the audience feel or empathize (regardless of the exact feeling).

While Counting New Beans focused on live theater performances (and my examples above followed suit), the study of intrinsic impact isn’t limited to theaters. A multidisciplinary study in Liverpool included theaters, museums, an orchestra, and other arts groups. I’d be grateful to hear from any local groups using intrinsic values data, either in describing their work or in assessing grantees. As I try to argue above, I think it’s a stronger depiction of the benefits of arts in our lives and provides arts organizations clearer and more actionable feedback than simple economic indicators.