Jamal was one of my closest friends in first grade. I don’t remember much about him, and have no idea where he is today, but most distinctly I remember the way Jamal interacted with the playground. The lower school playground was a good one. Built of wooden towers, its intended use was for people to stay within the Lincoln log-esque structure and climb to the top through a series of interior stairs, safely enclosed by four walls. Most of us abided by these rules, but not Jamal. I remember going to the third story of the playground structure, and looking up at the clouds while he threw one leg over the open sidewall, then the other, climbing down the outside of the tower to the second-story window below. Nothing under his feet, tips of his sneakers stuck into the structural holes intended for bolts, not for toes.

Jamal never got in trouble for his creative use of the playground equipment, but I remember thinking how he could have fallen and gotten seriously hurt. Playground equipment, designed to let children play and move without serious risk of injury, has never hit its stride of standardization. How safe is too safe? How much risk should we let children take? In a world where child leashes and swimmies are still seen on regular occasion, how do we balance risk taking with the seemingly ever-present safety net? While I have no children of my own, I do feel like the toddlers I see at the climbing gym are developing very differently than the five-year olds I witness buckled into an extended-age stroller.

I would imagine most of us conjure up similar images of a playground from our youth — a slide, monkey bars, swings, some sort of not-so-rickety bridge, and perhaps a metal jungle gym. I would bet all of us, at some point or another, misused this equipment: standing on swings, climbing on top of the monkey bars, or attempting to climb up the fireman’s pole rather than slide down as intended. These self-imposed challenges allowed us to overcome the standardized actions. We went up the slide instead of down, trying to make the soles of our shoes stick to the hot metal slope. We got our swings to go so high the chains refused to stay straight, tempted by gravity to buckle inwards. In the mind of an academic or sociologist, these actions demonstrate the need for a greater challenge. Dissatisfied with what is provided for us, we think about new ways to use our surroundings to provide unprecedented stimulation.

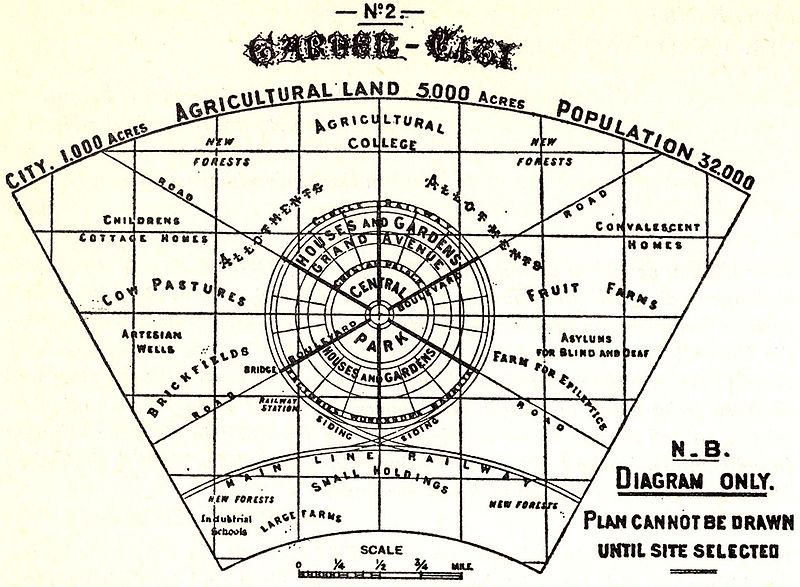

These actions aren’t limited to children. We witness envelope pushing in the teenagers skateboarding on steps or the parkour crews bouncing off walls and running across windowsills. Our environment presents us with the building blocks, we add the imagination to create interaction. In the urban environment and on the school playground, some manufacturers are changing things, in essence, to standardize creativity and risk. Playgrounds with small climbing walls or zip lines are popping up next to cargo nets. These features aren’t just for aesthetics, they’re meant to encourage increased physicality for kids — building upper body strength and helping hand/eye coordination. Urban planners and entrepreneurs provide similar opportunities — chess boards on sidewalks or built skate parks, interactive light installations or pop-up swingsets on promenades. These interventions encourage our imagination and allow us to change our behavior. The observation can even extend to bike paths; as greenways are created, we’re more apt to interact differently with our environment in a controlled fashion, rather than bicycle down a pedestrian promenade.

We can equate the benefits of risk taking to how adults react when a child falls. There is often a second, after a fall or a break, where a child isn’t sure what happened. They fall off a bike or get hit by a ball, and there’s a moment of silence where they collect themselves, and take inventory of what’s around them. The worst thing adults can do, my relatives profess, is to gasp. This harsh intake of air conveys worry, sending the message that the child might be hurt, and therefore, the child feels something is wrong and starts to cry. Several years ago I witnessed the opposite while ice skating on the Rideau Canal in Ottowa. Growing up with the world’s largest skating rink, kids were falling all over the place and no tears were shed. Falling was a standard risk of the physical challenge. During that key moment of silence, the adult wouldn’t miss a beat, “come on, get up, lets go.” There was no time to cry. This shift in normalcy from gasping and coddling to quick reassurance and continuation, I imagine, makes a huge difference in the willingness of a child to do more activities which might cause them to fall. It’s worth extending this attentive-parent worry to kids who don’t often have present supervision. Are those who fall and don’t risk hearing a nearby gasp of a worried parent more likely to play harder, go faster, and walk away from a fall with less perceived pain? I’d argue yes. when nobody is there to take care of you, there’s really no choice but to get up and keep throwing the ball.

In the daily grind where our senses are often dulled by a routine, these new and shiny installations are essentially new building blocks, challenging our minds to stretch more than usual — seeing our own piece of the world differently. Playgrounds are spaces where kids can learn from others in addition to pushing their own limits. Installing elements that encourage risk taking and help them conquer fear in a controlled environment are lessons many of us, I would imagine, wish we had the opportunity to learn ourselves.