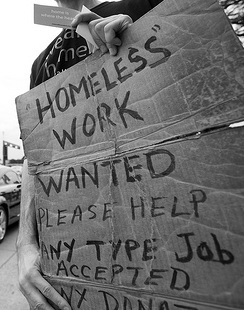

I’ve always thought of London as a friendly city. The only city to thrice host the Olympic Games, London hails itself as an welcoming destination city. That is, if you’re an Olympian, or a tourist. Not if you are experiencing homelessness.

Recently, London installed spikes outside apartments to prevent anyone from sleeping on the ground. The instillation came about a month after one man was seen sleeping outside. The one-inch spikes are not the first of their kind, and are known to exist in other parts of the United Kingdom and Canada. London mayor Borris Johnson, to his credit, called the spikes not only “anti-homeless” but also “stupid.”

He was not the only one. You may have even seen the spikes on social media, as outrage spread across London and internationally. Perhaps it was the political shaming, or the large-scale social media blitz that protested the spikes, but news reports indicate they were removed earlier this week.

This is hardly the first example of creating an environment unsuitable for homelessness. If you have ever looked at a park bench or a subway stop and wondered why the city planners were so worried about people having a place to rest their arms, they probably weren’t. Benches with multiple armrests, divided only wide enough to sit, are too narrow to lay or sleep on, dissuading homeless people from staying the night.

photo: TimberForm

Among all this techniques for making cities unwelcoming, a Canadian company created an installation that is both humanitarian and an act of advertising genius. Notice that not only do these city benches not have intrusive arm rests, but they actually prop open to create a temporary rain shelter. Inside are directions to a RainCity Housing, an organization that specializes in working with low-income individuals to meet basic needs.

photo: Huffington Post

Decisions as small as armrests matter greatly if that armrest ruins your bed for the evening. The steps we as city planners, politicians, social workers, and concerned citizen take to develop and improve our hometowns truly do affect the lives of many people, and these small injustices could easily go unnoticed if you are not the person impacted. This time, Toronto leads the way in providing both shelter and dignity to homeless individuals in Canada- perhaps other cities can also design a place for all residents, giving even the impoverished a place to call home.