My apologies in advance for the personal biases expressed in the following post, but not very big apologies.

Change takes place on so many different time scales that it truly boggles the mind: Geologic history is too slow to comprehend, and the speed of light is similarly beyond our everyday understanding. In any case, what we are really interested in is ourselves and those around us.

For the most part, this moment in history allows us to surf along on a sea of issues, each with their human connection, each one changing as social pressure influences and reacts to it. This is the story of one of these trends, and how it has influenced me, my family, the country, and the feedback loop that has changed the trend itself.

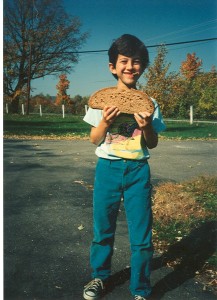

My parents started a bakery shortly after moving to Vermont in the mid-1970s, and their business has been cooking ever since, although with far greater attention to product quality than profit. Their small operation has not changed a great deal, growing slowly and shifting with their interests rather than with market pressures. They were the first organic bakery in the state, and probably one of the first in the country. (Check out some pictures and their story here, as long as you’re not already hungry!)

They have watched as the American consumer has gone from disdain to grudging acceptance, then cautious enthusiasm, then passion, and in the past decade, spastic cycling through rapid adoptions and rejections of the product they have spent a lifetime carefully crafting.

Their reaction? Mostly they try to ignore these market gyrations and just do what they want to, baking European-style sourdough loaves in their massive French hearth oven, working all the time, and raising a family of bread-loving children.

However, the changes taking place in public attitude over the past ten years have been something of a shock, and my folks and other artisan bakers have certainly had to acknowledge South Beach, Dr. Atkins, and all that followed in the low-carb frenzy that was intended to drop American pounds. The effect of the frenzy, by the way: Americans did not, overall, benefit substantially from their fear of carbohydrates, although the publishing industry certainly has enjoyed the ongoing attention to the issue (just shy of 6,000 titles come up on an Amazon search). My family’s business suffered a bit, but for the most part, it did not seem as though the followers of Dr. Atkins were the same ones who were ordering crusty, sourdough Whole Wheat loaves from our small organic bakery in Vermont.

This has continued to be the case over the past ten or fifteen years as the popularity of strict low-carb diets has waned somewhat, and I believe that this has been due to the separation between two segments of their customer base. On the one hand, there are what I will call Mainstream Eaters, brought up (like my father) on Wonderbread and Skippy, sticking to the traditional (i.e. large chain) grocery stores, and eating a diet that owes much to the cultural norms of the 1940s-1950s. On the other hand are my parents’ customer base, who I will call the Spelt Enthusiasts, a term I lovingly bestow on the many earnest, kind, birkenstock-wearing, kale-eating, home-made-granola eating hippies and their children (of which I am one, of course) who have come to my parents for decades seeking whole grain breads, made by hand using traditional methods. (Spelt, for the uninitiated, is an ancient variety of wheat which has experienced relatively little hybridization and has a somewhat nutty flavor.)

The separation between these two groups has narrowed in recent years, moving in the general direction of the Spelt Enthusiasts as a greater foodie culture has spread throughout the country. The narrowing of this gap has had an enormous impact on our economic and food systems in the U.S., (and arguably the world) as there is now a far greater interest in organic, local, artisan, hand-crafted food and beverages. This trend has given a degree of market power to local producers that has been absent for generations- perhaps since the Industrial Revolution.

Although I would hesitate to describe this as ‘unprecedented,’ as I am not a historian, it isn’t a stretch to refer to this market transformation as amazing. Despite the awesome power of industrial farming, baking, brewing, cooking, packaging, and shipping technologies, individuals using essentially the same ingredients and techniques as their great great grandparents are launching successful bakeries, restaurants, breweries, and cheese making operations all over the country.

Time to circle back to the title of this piece. The challenge my family faces is the latest iteration of popular science writing, which had previously focused on folk neuroscience and psychology- issues that passed bakers by other than our passive consideration while listening to the radio and rolling baguettes. The cold, hard pen (or keyboard) of scientific terminology and rationale has turned to the issue of diet. The demon of this recent dietary focus is, of course, gluten – the web of proteins that allows bread to rise from a cold, dense piece of dough into a transcendent, glowing, golden loaf crying out for a slice of cheese and tomato. We should be concerned about blind trust in scientifically justified behavioral recommendations with very limited scientific basis.

As Alissa Quart points out in her 2012 NYT piece,

…bogus science gives vague, undisciplined thinking the look of seriousness and truth.

Regardless of your opinion on the issue, there are some facts that most agree upon.

1. Celiac Disease affects .7 percent of the population, many of whom are undiagnosed. The most effective strategy for those with Celiac Disease is to avoid gluten altogether.

2. Allergies to wheat may affect as much as 3 percent of the population.

3. Less clear, but still generally agreed is that a slightly larger group has gluten sensitivities, but not full blown Celiac. This number may be as much as 6 percent of the population, with a very wide range of severity, from profound to scarcely noticeable.

What I feel is missing:

1. Many people do not know what gluten is or where it comes from. Look at the products now proclaiming their gluten free status. Hummus? Juice? Cheese? There is a massive amount of money to be made on gluten-free products right now, and companies are taking advantage of uninformed consumers. How much of this is being driven by profit? It makes an honest assessment of health impacts very challenging.

2. A sense of perspective. Like most effective diets, giving up gluten involves a far greater amount of attention paid to what you ate eating. There is a need for balance, more fruit, vegetables, and legumes, while moderating the intake of animal proteins. If following such a diet makes you feel better, it could be the gluten, or it could be the effect of giving what is on your plate some truly conscious thought.

Celiac Disease is an extremely challenging condition, requiring sacrifice and discipline in order to stay healthy. Those who suffer from it are torn about the recent spike in gluten-free diets, appreciating the diversity of options now available, but frustrated by those who have simply jumped blindly onto the bandwagon.

3. Fads. There is nothing like a fad to push a business operating with high overhead and a reliance on a stable market into a situation that threatens the owners and employees.

People who love eating good food should take the time to be certain that giving it up is a wise health choice. Eating good food is one of the most easily accessible and most important ways to affect the health of individuals and their families.

Fads end eventually, and the artisans responsible for providing high quality bread can only remain in operation after the gluten bubble bursts if conscientious consumers continue to support them. Thanks to the changing attitudes about food and farming practices, these craftsmen and women are likely to be your friends and neighbors, not line workers at an industrial food factory 5,000 miles away.

Additional image credits to Chuck and Carla Conway, with assistance by archivist Sophie Conway

Pottery class starts next month, by the way! Sign up soon to get muddy and make pots!

To clarify what this post is and is not:

Although I am confident that a strong scientific rebuttal can be made to the wave of gluten-intolerant articles, books, and the like, since I am not a scientist, I am not the best person to make such an argument.

Instead, I would prefer to advocate for good, healthy food and making efforts to support your local economy.

While I very much appreciate your post, and I do agree with you and applaud you for advocating ” for good, healthy food and making efforts to support your local economy,” there is one thing I’d like to address. I used to think that labeling products like hummus or orange juice as gluten free was a marketing gimmick (and perhaps it still is), I am now grateful that more companies are doing this because I was recently diagnosed with Celiac Disease. I never knew how many things had gluten in them before. I don’t eat a lot of processed foods, but I do buy some prepared things (mustard, etc.), and you’d be surprised how many of those things, including from the most “natural” and organic brands, contain gluten. Anyway, just thought I’d share how my perspective has changed.

Thanks Shoshannah. We very much appreciate you adding your perspective to the discussion. I’d be curious what resources there are out there for people who have recently been diagnosed with Celiac Disease to guide them in their dietary choices.

You bring up a great point and I think there are actually several points in history where our dietary choices have dramatically shifted over a nutrition belief that does not precisely match up with scientific realities. Take the lipid hypothesis which made fat into the demon it is known as today. You ask anyone what they need to be heart health and they’ll tell you to cut out cholesterol and fat. Yet the science if far more complicated and the link between dietary cholesterol and saturated fats with heart disease is murky.

I think your point of being more mindful about what we eat and what’s in our food is a good one. To Shoshannah’s point when you have an allergy you learn quickly how complicated it can be. My college roommate was allergic to soy and it was really hard to find food she could eat. Vegetable oil is generally soy oil and the compound that makes cheese yellow is soy based. I would have never thought to label cheese “soy free” (unless it was that vegan ilk) until I met her.

So then how do we make the public more aware of what they are eating and less susceptible to food trends? Especially when government agencies often tend to jump on the food fad bandwagon.

Thanks for the comment, Shoshannah, I appreciate your perspective, and you make some good points.

Modern food production often include a great number of ingredients that are difficult to interpret (at best), and as you say, many of those additives are naturally derived. If there was ever a moment to be diagnosed with Celiac, this is probably that moment, as producers are motivated by market pressure to provide that information in bright, bold lettering.

However, the target audience is unfortunately not you or others with the condition. Since the mid-1940s when it was firmly linked to wheat proteins, those with Celiac sprue have pleaded with food makers to label their products and create additional options, but their numbers are far too small to exert market pressure. Although beneficial, it’s a shame that the critical shift was caused not by or for those with the greatest stake in the issue but rather for those interested (however earnestly) in the latest foodie fad and the publishers and producers aiming for profit.

However, for you and others with this serious challenge, I am truly thrilled at the wealth of options now available!