A few days ago the ‘Black Guy Breaks into Car’ video popped onto my radar. It, like its 2010 bike theft predecessor on the What Would You Do? show was proof that *gasp* black and white Americans have different realities in how they’re treated on a daily basis.

Really? Despite the facts that, though making up only 14 percent of the population, black men account for 40 percent of all prison inmates; though stopping rates are the same for whites, blacks and Hispanics, blacks are three times more likely to be searched (person or vehicle), more than three times more likely to be handcuffed, and almost three times more likely to be arrested; and depictions of blacks in television and movies is of criminals, reformed criminals, people with rough or ‘street smart’ backgrounds, or auxiliary comic relief to their white (and Asian) counterparts, there are still those who live their lives believing everyone in America is treated equally.

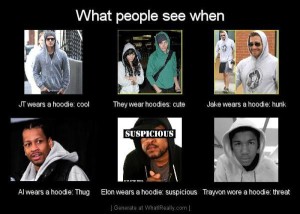

Let me clarify. To be black is to be automatically viewed with suspicion while to be white is to be assumed blameless until proven otherwise.

Blacks in America are at a crossroads of perception, reality and environmental circumstance. Though Black households give 25 percent more of their income to charities than their white counterparts, they are often depicted as selfish and opportunistic. And while Black youth make up only 16 percent of public school students and 9 percent of private school students, they account for: 35 percent of in-school suspensions, 35 percent of those who experience one out-of school suspension, 46 percent of those who experience multiple out-of-school suspensions, and 39 percent of those who are expelled (from Black Stats: African Americans by the Numbers in the Twenty-First Century by Monique W. Morris).

So, how do those of us not wielding a camera work to combat these misconceptions and prejudice?

As my last post suggested, you could cross neighborhood and comfort zone boundaries by trying out a new restaurant in a place you don’t normally frequent, or follow Robyn’s advice to spend money locally in off the beaten path shops in ignored places.

There’s another, more convenient (but in no way easier) way for most of us to fight injustice: your voice.

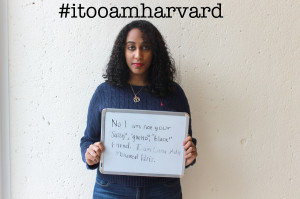

The microaggression awareness movement has begun highlighting the unintentional and thoughtless yet hurtful things we say to one another on a daily basis. I’ve been called ‘Cosby Black’ on more occasions than I care to remember and have painful flashbacks to being taunted as an ‘Oreo’ when I was younger. The tumbler, ‘I too, am Harvard’ displays how even those at the pinnacle of American education are saddled with the prejudice, labeling and misrepresentation of past generations.

Part of the “I, too am Harvard” Project

If prejudice is ever to be overcome, it will take daily acts of consciousness. Mind your words, avoid attributing an entire race to one person and maybe you’ll make someone’s day a bit less cringe-worthy.