So much of establishing metrics and evaluations for an organization or program is about asking the right questions and sometimes those questions take you unexpected places. For Rebecca Yenawine and Zoë Reznick Gewanter, their questions have led them on a multi-year research project encompassing not only the outcomes of community art projects, but also illuminating the meaning and merit of the field itself.

Yenawine and Reznick Gewanter are both involved in MICA’s Community Arts program (Yenawine is an adjunct faculty member and community art evaluation consultant and Reznick Gewanter is a graduate of the Masters of Art in Community Art and research assistant for studies through the Office of Community Engagement) and collaborators in the Reservoir Hill-based youth media nonprofit New Lens. In pursuit of useful evaluations for New Lens, the pair realized more contextual research was needed in the area of community art. They’ve designed and are in the process of completing the following three-phase research project:

- Phase I (2010): Conducted 14 national interviews with community arts practitioners with ten or more years experience.

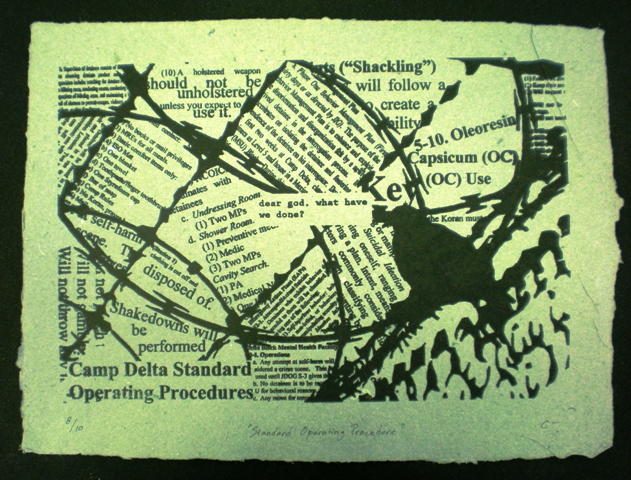

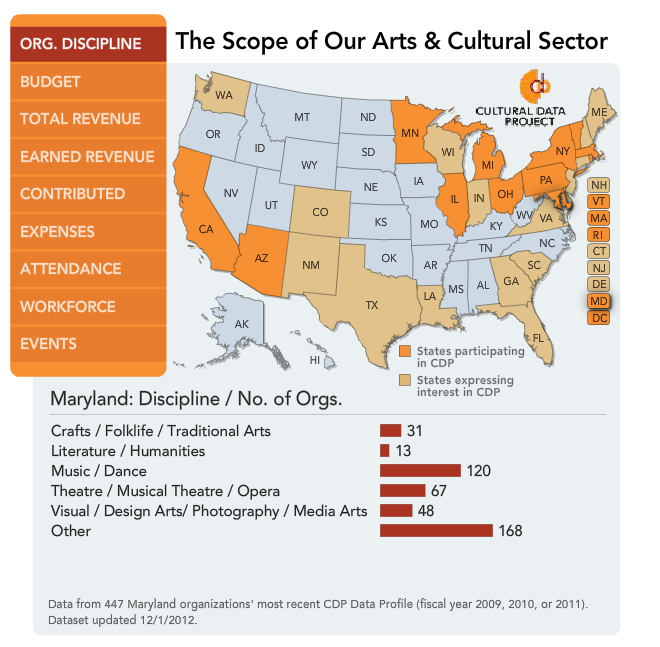

Outcomes of community art cited by current practitioners in the study. Source.

- Phase II (2012): Interviewed more than 80 youth participants of Baltimore community arts programs.

- Phase III (ongoing): Studied the impact of community arts programs in five Baltimore neighborhoods (four with active community arts programs, plus four control neighborhoods), collecting 1,000 surveys.

As a whole, this research looks to document the impacts of community art in order to help other practitioners, organizations, communities and funders. This sort of broad multidisciplinary research is rare and provides a benefit to the entire field. In its first two phases, the study provides a common language with which to discuss outcomes in community art, and the final phase includes the development of an assessment tool that can be adapted across organizations and communities. In addition to better describing the outcomes of community arts programs, the research of Yenawine and Reznick Gewanter also challenges practitioners and organizations to invest in evaluations that are specific to the impact and influence of the field and not simply generic metrics. On the Americans for the Arts web site, Yenawine writes:

If art is in fact offering a space for developing social understanding, for connecting and building relationships, and for developing greater cohesion, part of the story that needs to be told is about how and why this is a valuable counterbalance to a society whose bureaucracies emphasize productivity, economic success, and competition without fostering the larger social fabric of communities.

This is really the value of outcomes and metrics. Data is more than numbers in a spreadsheet, charts submitted with reports; at its best, it empowers our descriptions and understanding of our communities, our work and their merit.