At noon on Saturday I sat in a white rocking chair on a front porch. A springer spaniel sat at my feet, a strawberry beer in my hand. I heard birds. I was confused.

“So wait, this is considered the City? We’re within the city limits?”

A fellow planner and I were in Charlotte, North Carolina, and I was trying to wrap my head around a place with front yards, back yards, and heavy tree canopy. It didn’t seem right to equate that landscape with the term “city.” I had landed the night before and promptly dozed off in a taxicab. it took me several minutes to figure out what was different about where I was, as we zipped through the wide roads under the night sky. It wasn’t the warmth I’d been seeking for months, and at first I figured it was the absence of sirens and police helicopters I’ve sadly become so attuned to living in Baltimore City. Halfway through the taxi ride, I realized the difference was an overall silence. I was surrounded by skyscrapers in the central business district at 9pm on a Friday night, and there weren’t any people anywhere.

I had too many things to write about this week — dangerous playgrounds, airports, my newly formed place-making theory which I’m dying to put in front of an intelligent audience. But as I drove along the empty streets of a 2.96 million person metropolitan area, I realized I needed to write about people — the ones I love to hate, the ones in my way, who talk too loud and hang out too late. When I step back, I realize these people are part of the Baltimore urban fabric.

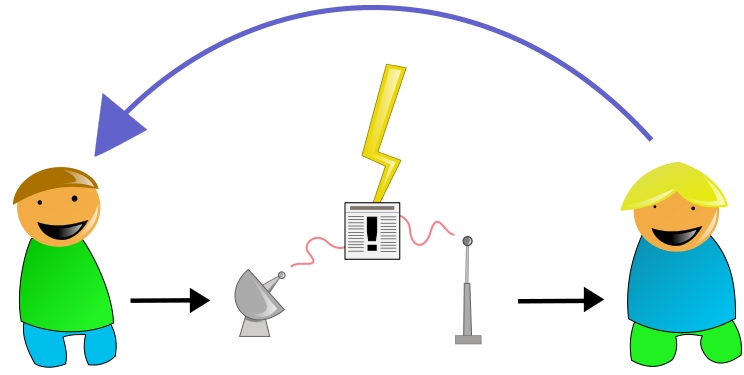

My first conscious encounter with the urban tradeoff happened on the island of O’ahu, Hawaii, where the Aloha spirit became a bit too much to bear. The rainbows which constantly littered the paradisaical sky became commonplace, and after months of living on the island I found I hardly noticed colors amongst the clouds. I missed thunder and lightening, and realized if I lived in Hawaii, I would be sacrificing those beautiful summer storms for good. Would the tradeoff be worth it? Could I trade in thunderstorms for rainbows? A similar thought came to me during that Carolina cab ride: would I give up the noise of the city for a place that goes to sleep at sundown?

There are people I know, and who you might know too — the more infamous loiterers of Baltimore who I’ve found myself apologizing for. The woman who ran across Boston Street on a whim with her shopping cart, screaming obscenities as you tried to screech your 40mph traveling car to a halt. The kids who hang out in the alleyway behind my house and talk too loud and too late, my neighbors who sit on their stoops and the kids who climb Clinton Street trees and the late-night Patterson Park walkers. Would my life be emptier without these people? If they disappeared from the streets for good would I be satisfied with the silence?

Instead of front porches, Baltimore has stoops. A little piece of earth we can safely call our own. These stoops aren’t just decorative, they foster neighborhood involvement and the built-in abilities for us to know our neighbors and keep an eye on our street. For those few hours of rest, we can survey our surroundings from a street level, rather than separated from everyone else on a back porch. Stoops have become engrained in our culture, from specialty-marketed cleaning products for stoop cleaning and inspiration for storytelling.

If you drive through the city at 9pm on a Friday night, you’ll see people out and about — and those who aren’t necessarily going anywhere, but who have simply found a great spot to sit, and look at everyone else. This is the beauty of more and more people living downtown — the fact that as much as I miss nature, if I’m going to live in a city, I want it to be vibrant.

There’s something wonderful about being able to sit at the street level. We fight for parks and public spaces, as well we should, but let’s not forget our own opportunities to populate the little bit of marble and outdoor real estate we call home.