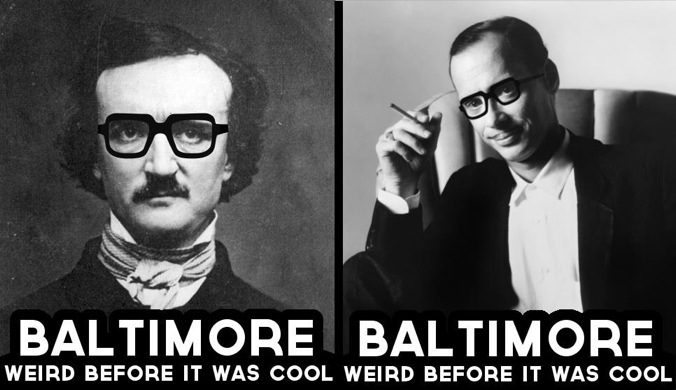

A few weeks ago, ChangeEngine challenged us to come up with a tagline for Baltimore. The one I chose was a spin on the Keep Austin Weird campaign:

Keep Austin Weird is a slogan created by Red Wassenich and adopted by the Austin Independent Business Alliance to promote local business in Austin, Texas. It has been seen as a huge success in celebrating the city’s tolerance, innovation, and local flavor. The campaign has spawned hundreds of knock-offs including Keep Portland Weird, Keep Ashville Weird, and even the small town in Virginia where I am currently writing this has a Keep Staunton Weird campaign.

While I love the celebration of quirk, seeing the campaign through the lens of Baltimore brings some interesting questions to light that I am going to explore in a three part series. Over the next weeks I will look at the Keep Austin Weird campaign and ask three key questions:

- Who gets to define weird?

- Who benefits from weird?

- How can we celebrate a weird economy?

The first question hit me when I was reading Lindsey Davis’ blog this week on “Embracing the Noise.” Often times the “Keep Weird” campaigns focus on businesses or festivals that define the city but in reality some of our favorite things about our locale is the people you find on the streets. The “Oh Baltimore” moments people have shared this past week with ChangeEngine show a side of Baltimore often not embraced by people who try to brand our city, but nevertheless are one of the reasons we stay.

This brings me to my first question: who gets to define weird? One of the criticism of the Keep Portland Weird campaign is that it only celebrates the young Portlandia generation and not the original residents of the Oregon town. Most campaigns generally only celebrate brick and mortar local businesses, excluding hustlers like the amazing makeshift market that appears daily on the corner of 25th and North. Keep Weird campaigns tend to focus on gentrified areas where local businesses thrive and problems are kept at bay.

We often deny that weird can sometimes be uncomfortable. The man who shouts at you for no apparent reason, the group of loiterers who mingle at the bus stop on the corner, the person who asks you for money every time you leave the grocery store are all part of the city too but rarely are they symbols of any Keep Weird campaign. This is why I love guest blogger Devan Southerland’s love note to Lexington Market. When you watch the lost tourist souls, bravely venturing from the Inner Harbor, their wide eyes desperately trying to get a Findley’s crab cake, you realize like tourists in every city they fail to see what truly makes this city incredible. It is not the crab cake that defines Baltimore, it is the people you have to weave through to get there.

In Baltimore everyone defines our city. It reminds me of a line from “Good Morning Baltimore” in John Waters’ Hairspray:

There’s the flasher who lives next door

There’s the bum on his bar room stool

They wish me luck as I go to school.”

It seems like Baltimore has always been defined by its more seedy elements. After all, our most famous resident died in a gutter. The most popular TV show about the city is The Wire putting the city’s problems and complexities in full view. This is why most people outside of the city give me a skeptical look when I describe the city as magical. On the surface Baltimore doesn’t seems like the king of weird. We have nothing to compare to South by Southwest, we’re not the live music capital of the world, we don’t have a robust local business scene, and while growing everyday our population of hipsters has not yet sufficiently taken over the city to turn it into the next weird colony.

What we do have is a redefinition of weird that is more than a celebration of gentrified funkiness. Our “Oh Baltimore” can be simultaneously uncomfortable and endearing. It is a city where “the sketchy” part of town is only two blocks away from “the nice” part of town and no one can hide from our city’s problems. As with most major cities we have our divisions and deep rooted problems, yet unlike most cities our grit is what makes us iconic. Our weird is what unites us. It doesn’t solely reside in AVAM or MICA or Hampden, it is on every corner, it relaxes on stoops, it dies in gutters, it lives in bustling markets. That’s because Baltimore was weird before it was cool and we’ll be weird long after.