After sitting and writing for an hour on how urban planning can encourage safer spaces for women, I recalled another article I read this week entitled “Bad Urban Planning is Why You’re Fat.” I had little tolerance for the article. Sure, maybe many of you live on cul-de-sacs. Perhaps you live on the side of a highway and have reduced walkability. Is it my fault you’ve chosen to eat Cheetos instead of an apple? No. The innate mentalities of individuals are going to dictate their actions regardless of setting. So while I composed an entire article on well-lit spaces and planning measures needed to reduce crime, I realized that a woman in danger is going to be a woman in danger, no matter how well lit a public space may be.

When it comes to conquering the city, I have this underlying sentiment of invincibility allowing me to believe I can walk home risk free at 3am. I realize this is far from brilliant — I realize I tempt fate: walking barefoot around Rio at 4 a.m. because I’d thrown my shoes over a gate, sharing a taxi with a stranger for six hours en route from village to village in the middle of at third world country.

If you are male and of the six-foot-I-can-punch-people variety, let me break it down for you. Traveling as a woman, whether in Baltimore or Egypt, is a very different experience than the one you have. We’re constantly talked to, approached, stared at, and solicited without invitation. We’re seen as weak and conquerable, making us a seemingly easy target for those looking to do harm to others. Because of this we often look down, walk more quickly, and are potentially more bitter or hesitant about our trip down the road. For the record, catcalling turns us off, it’s fucking rude, but this isn’t a piece about your failed pick-up technique. It’s a piece about the good and bad people, and where they choose to roam.

I know well enough to leave a dangerous area when I feel uneasy. I know well enough to cross a street if someone is following me or be wary of the man watching me from the rooftop. I’m perceptive, and I successfully avoid the dark alleyways and sunken sidewalks — but it isn’t a place that will prevent me from being attacked, it’s the people who frequent the places where I choose to go.

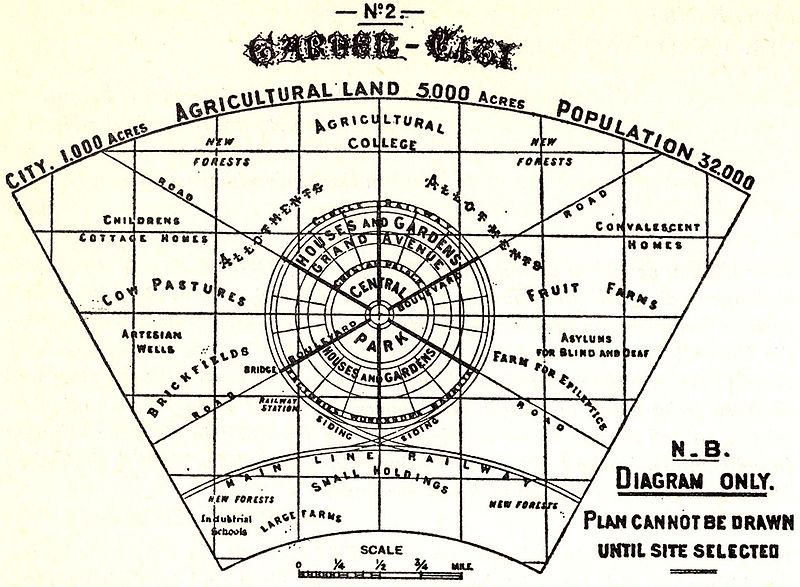

Neyaz Farooquee wrote an excellent piece in the New York Times this week attempting to link India’s city planning to the propensity for sexual violence. Farooquee cites human presence and sidewalk lighting as deterrents for violence against women. Another article in The Atlantic Cities cites adds to this list, citing gated communities and stop signs, attempting to correlate vehicle stops and space ownership with gender-specific violence. The truth as I see it, is that bad things are going to happen regardless of space design. Yes, a dark alley will make it easier for a crime to take place without external observation, but assuming that a changed landscape will eradicate the desire or need for someone to tap the vein of maliciousness is ridiculous.

While I, without a doubt, recognize the importance of designing places so they can be perceived as safe spaces, I’m going to be on my guard no matter where I find myself. No single space is going to negate the presence of, for lack of better term, bad people. Not security gates, not the perfectly designed parks, not a secure school. Yes, urban planners should design engaging places that get people outside, regardless of gender, and make them want to walk the roads paved with good intentions. But changing the behavior of the individual is not in our jurisdiction.

Through design we can encourage or discourage gathering, we can make it possible for people to move without needing a personal car, we can put a grocery store on your corner or far away, we can put in a playground — assuring no sexual predator can be within 1,000 feet. What we can’t do is police the neighborhood and drive home the sentiment that targeting females is bad. If someone is intent on causing harm, I think it’s a safe assumption to say they’ll find a way, despite whatever barriers the planner has put in place. At the risk of cheesing my way out of responsibility for the greater good, the issue is societal. Planning can only do so much. And on that note, if you figure out a way to stop the unsolicited catcalling through the built environment, you let me know — because you, my friend, would be a far better urban planner than I.