I was heavily involved and invested in museums for the first decade of my career — as a staff member, a fellow, an intern, a volunteer and a museum studies student. So it was a delight to attend the annual meeting of the American Alliance of Museums in Baltimore this week, greeting the people in the field that I follow avidly via Twitter and blogs and the icons of the museum world to the city of which I’m such a fan.

Photograph of AAM program/schedule courtesy of Michelle Gomez and via Instagram.

The theme of this year’s conference was “The Power of Story.” And while that might not seem that relevant to data and evaluation on first glance, it’s data that gives power to our stories. Inside museums, evaluation and measurement are done in some ways that might be familiar to the casual visitor (e.g., visitor surveys, comment cards, program evaluations), but also some that might be unexpected or go unnoticed, as a profile from the Wall Street Journal illustrates:

Matt Sikora doesn’t look at the Rembrandts and Rodins at the Detroit Institute of Arts. His eyes are trained on the people looking at them. Mr. Sikora watches where visitors stop, whether they talk or read, how much time they spend. He records his observations in a handheld computer, often viewing his subjects through the display cases or tiptoeing behind them to stay out of their line of sight. “Teenage daughter was with, but did not interact, sat on bench, then left,” read his notes of one visit.

It’s not uncommon for museum evaluators to shadow visitors in the galleries, learning from their movements what areas or objects are engaging and for how long. In addition, before an exhibition opens to the general public, many elements, including label text and interactive gallery displays, are prototyped and tested. Through these evaluations, exhibit designers, curators and museum educators learn more about visitors’ reactions to exhibits: which elements are engaging, confusing or overlooked. In addition, some evaluation tools also provide information about what visitors take away from their time in the gallery — what was learned, what inspired them, what connections they made and, hopefully, what will draw them back again.

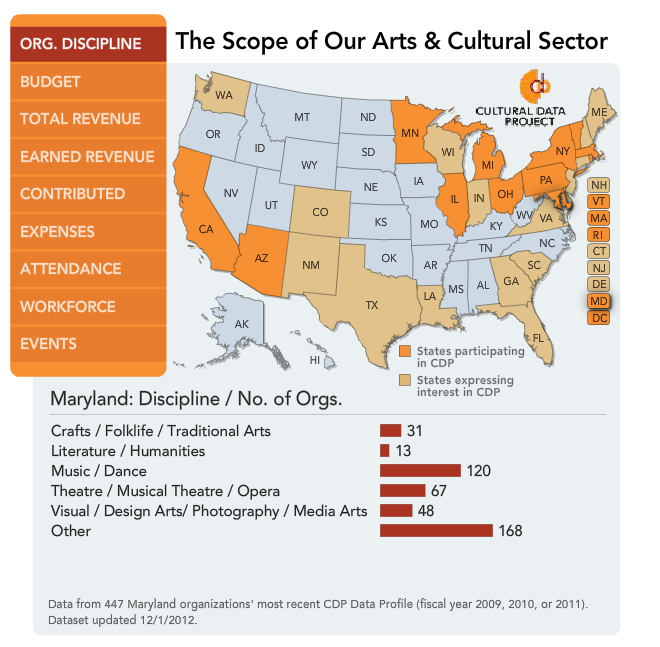

Beth Tuttle of Cultural Data Project: The big question isn’t what is the data or how do you use it, but WHY does it matter? #aam2013

— ESI Design(@ESIDesign) May 21, 2013

What was so empowering about this year’s conference was being able to evaluate those tools themselves, and to learn. Surprisingly, technology is not always the answer. Visitor evaluation consultants and staff members from the Brooklyn Museum and Monticello shared various scenarios where their attempts to survey visitors went awry because technology got in the way or skewed results, the target audience was elusive or just straight-out avoided their polling attempts. It just goes to show that even bad data can teach you something, even if it’s not what we set out to learn!

Even more surprising was the lesson that data doesn’t necessarily persuade, no matter how clear or comprehensive. Often, beliefs trump facts. As Stephen Bitgood, Professor Emeritus of Psychology at Jacksonville State University and Founder of the Visitor Studies Association, said, “When strong belief is pitted against reason and fact, belief triumphs over reason and fact every time.” Despite our expectation that data should persuade, prove and set people on the right course, it simply doesn’t override gut instinct, what people feel or believe to be true. Again and again, presenters told tales of data being met with questions or disbelief. Unfortunately, no solutions were presented to either circumvent or resolve this issue, but I am filing this under “knowing is half the battle” and keeping it in mind when data is presented as all-powerful or all-knowing.

Photographs of AAM display, top to bottom, courtesy of Mariel Smith via Instagram

and Lindsay Smilow via Instagram.

So evaluation and measurement can fail or go awry. Testing our tools and techniques in small batches prior to rolling out the full survey or other strategy gives us an opportunity to see it in action and identify areas to fix or improve. If evaluation and measurement are treated as afterthoughts, as so often is the case, these tests are even less likely to occur and, as a result, the final data may prove useless, further cementing the idea that evaluation itself is a useless activity. It’s a difficult cycle to break out of, but worth identifying and tackling so that we can truly tell a more powerful story.