For the past four weeks, I have been working for the Baltimore Design School. I’m convinced that design changes humanity and that our pedagogy will transform our students’ lives. Design makes finding a place to stay along the super highway of information easier. It makes us look good. It makes us feel good. Design influences human experience. But how do you teach design to 12-year-olds so that it sets them on the trajectory to success? Recently four thoughts have resonated as I contemplate what design is all about…

Design is about details. Steve Ziger is one of the co-founders of the Baltimore Design School. He is also the principal architect of Ziger/Snead, the firm that designed the new $27 million dollar building that is shaping a future of Baltimore city filled with designers. He is excited about many MANY aspects of the physical building but there are some bits of information that he is giddy to share with just about anyone who enters.

“Did you notice the buttons?”

A number of the sinks — yes, bathroom wash basins — in the building were generously contributed by a local concrete firm. Embedded into a number of those sinks are buttons. Clothing buttons to be precise. Those buttons were salvaged from the building. Prior to its 30 years of abandonment, the building was the home to the Lebow Coat Factory. Those buttons are a nod to the rich history of the space. They are a minute detail that captures much more than physical space.

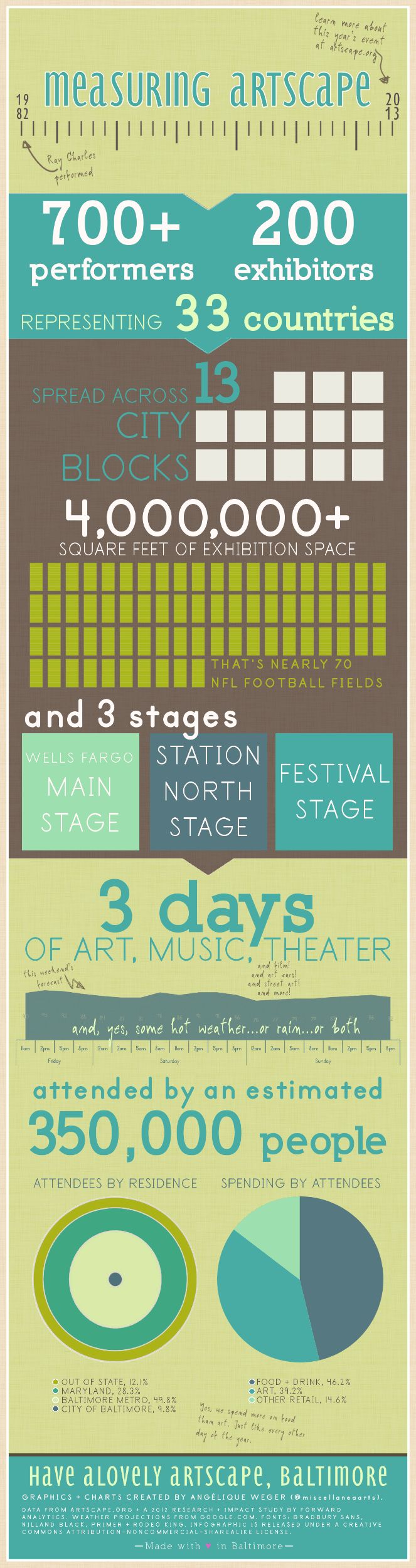

Design is about collaboration. Fans of “Mad Men” can probably tell you who the driving force of creativity is for Sterling Cooper Draper Pryce. Don is the man. Similarly many non-architects could name a few of the 20th century’s most famous visionaries of 3-D art. The genius of the individual has been on display through much of history. Things have changed. Ideas and information are accessible to far more than the guy with a 150 IQ. In 2013, and likely beyond, it is teams and collaborative efforts that will create masterpieces time after time. Good design is design that has many perspectives to shape it. The design school building abounds with spaces for designers, staff, and community to gather and discuss.

Design is about the audience. Paul Jacob III spent the better part of the early 2000’s leading RTKL. The respected firm has imagined and created breathtaking buildings that span the globe. In a conversation about design, Jacob said that “one of the happiest moments for an architect is taking a client into a building and them seeing that it is theirs. It is their story, their message and their vision.” Good design is about the audience and more importantly, audience ownership. Much like art, engagement and expression moving beyond the creator is extremely important. The common areas of the Baltimore design school are gallery spaces. Many of the walls of the hallways, cafeteria and gathering areas are “tackable” surfaces. What is created in the classrooms is not truly complete until it has been shared with others.

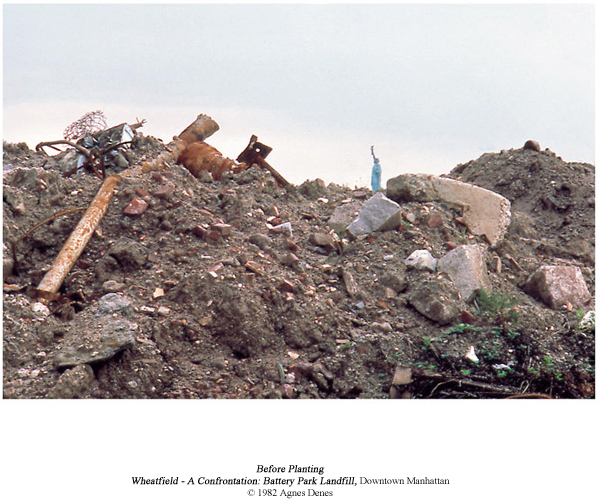

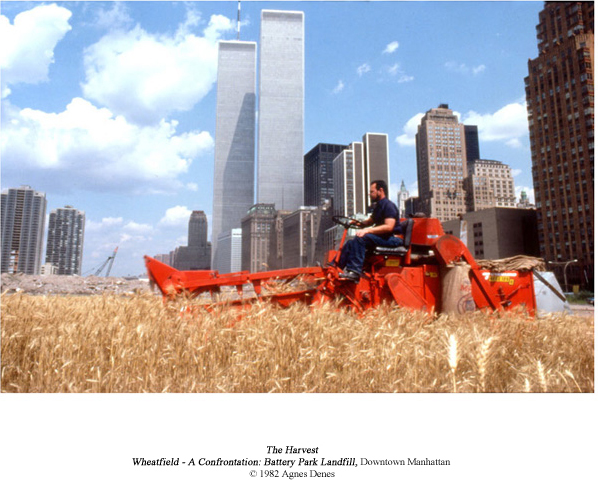

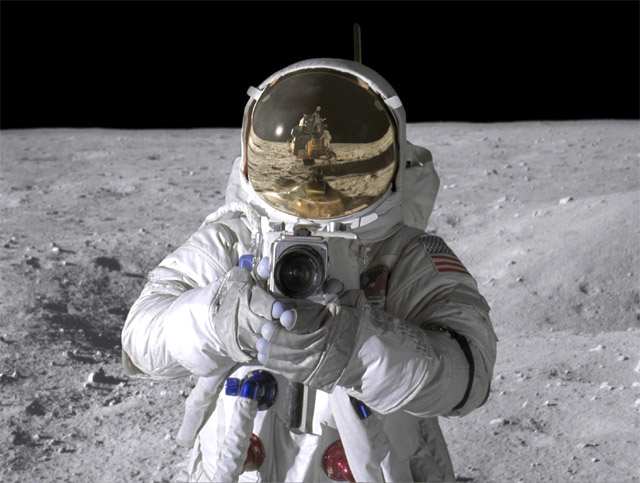

Design is about unexpected relationships. John Maeda is the president of the Rhode Island School of design. RISD is among the greatest institutions of artistic education in the world. In a 2012 TED talk, John cited the ability to make connections where no one else can as the essence of what good design is all about. It is the surprising placement of two distant colors next to each other. It is the introduction of two polarizing personalities that creates a global enterprise. It is the connection between a state senator and the president of an art institution that created Baltimore Design School. It is the use of a hundred-year-old building to educate the future change-makers of Baltimore city.

IMAGE CREDIT. [www.baltimoredesignschool.com].