Since this column started, one of the topics I’ve read the most about and wanted to eventually cover has been creative placemaking. Those two words, placed together just so, were so full of intrigue to me and seem to provide an umbrella under which all my other public and community art interests are sheltered. I was introduced to the phrase “creative placemaking” when I met Deborah Patterson of ArtBlocks at CreateBaltimore in 2011. Because our meeting was a brief one—pretty much throwing our business cards at each other and saying we liked what the other was saying in the last session while running off to a new session—it didn’t really provide me any context for the phrase. And then, as so often happens, I suddenly was encountering the phrase everywhere (this is called the “Baader-Meinhof Phenomenon,” by the way—you’re welcome!).

Eventually, I dove into some research and discovered the National Endowment for the Arts‘s (NEA) basic definition of what creative placemaking is:

In creative placemaking, partners from public, private, nonprofit, and community sectors strategically shape the physical and social character of a neighborhood, town, tribe, city, or region around arts and cultural activities.

In order to be or appear inclusive, prepositional phrases have been hitched all over the place to this definition, and I find it all quite gets in the way of understanding what it’s all about. Breaking out the red marker, the definition can be whittled down to this:

In creative placemaking, partners strategically shape the physical and social character of a neighborhood around arts and cultural activities.

The NEA’s definition matters a lot to people not just because of their role in influencing thought, but also because they have a grant program specific to creative placemaking. The Our Town grants were launched in 2011, and, over the last two years, have provided $11.58 million in funding in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. However, even in its simplified form, this definition is too wordy for a tweet and still manages to lack specificity. ArtBlocks’ mission statement cuts through all that and includes a definition that is tweetable and understandable:

Our mission is to provide communities with creative placemaking, a grassroots, bottom-up design tool used to identify their goals for their public spaces.

I gravitate toward this definition because:

- It identifies that placemaking is a tool. In the NEA definition, creative placemaking just sort of is. It might be a collection of strategies, but that’s not super clear.

- It creates a sense of ownership: Creative placemaking is for communities, their goals and their spaces. The NEA definition names a lot of players and a lot of places, but it doesn’t establish that the power in creative placemaking is bottom-up and is within the communities themselves.

- As is evidenced in the very existence of this blog, I’ll always choose concrete—and hopefully measurable—goals over “strategically shap[ing] the physical and social character” of anything.

Of course, there isn’t a shortage of definitions for creative placemaking and just because I found one close to home doesn’t mean I stopped collecting them. The Project for Public Spaces (PPS) is the grand-daddy of creative placemaking organizations; they’ve been at it since before I was born and play an active role not just in projects that have a placemaking approach, but also in terms of promoting placemaking and providing resources and training for individuals and other agencies. Back in 2006, they asked for individual’s definitions of placemaking and the resulting list represents a variety of perspectives, some frustratingly broad, others inspirational. My favorite states:

[Placemaking is] the art and science of developing public spaces that attract people, build community by bringing people together, and create local identity.

The latter portion of this definition reminds me of some other ChangeEngine posts on branding cities and Baltimore specifically and works for me when I tie it back to ArtBlocks’ emphasis on communities (or neighborhoods or tribes or cities) having the power to create and emphasize their own identity. Unlike so many efforts that focus on bringing in tourists, creative placemaking has the opportunity to be about the community itself and have a result that may or may not be meaningful or attractive to outsiders. It certainly can, but it needn’t be; it doesn’t have to justify itself based on the number of hotel beds filled, for example. (Which isn’t to say creative placemaking doesn’t have to justify itself at all; more on that soon!)

In addition, while I don’t look to diminish the impact of the NEA’s funding—Station North was a recipient of one of the inaugural grants, afterall—it’s certainly not the only way for creative placemaking to occur. PPS specifically highlights and encourages a “lighter, quicker, cheaper” approach to placemaking:

Whether you want to move your office outside, organize a citywide cooking festival, or start small by making a concerted effort to engage directly with your neighbors every day, know that your own actions are an essential component of your neighborhood’s sense of place, by virtue of the fact that you live there. […] Great places are not created in one fell swoop, but through many creative acts of citizenship: individuals taking it upon themselves to add their own ideas and talents to the life of their neighborhood’s public spaces.

While creative placemaking may seem like a fad or be dismissed as something frivolous, definitions like those provided by ArtsBlocks and calls to action like those issued by PPS remind me that place matters. The sense of ownership and identity related to place are strong motivators; you hear it in the arguments between sports fans — we’re seeing it in the images from Gezi Park.

This post, of course, is just scratching the surface of creative placemaking. Future installments will focus on specific placemaking projects and successes in Baltimore and also rumblings about the role of outcomes and evaluation in creative placemaking. And, for those of you reading who still question if creative placemaking is useful or effective, I leave you with these words from architect Jody Brown and encourage you to click through and enjoy the photos and the rest of this piece:

Thank you public plaza, for giving pigeons a place to poop.

Thank you public plaza, for flooding whenever it’s humid.

Thank you public plaza, for that patch of green in that concrete planter over there. I had almost forgotten about nature.

Chanel, anyone?

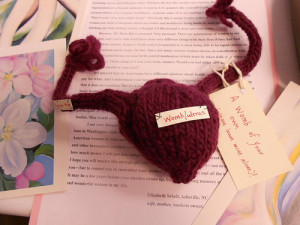

Chanel, anyone? A knitted uterus sent to a North Carolina senator.

A knitted uterus sent to a North Carolina senator.