The Northern border of Mexico, a hotbed of drug trafficking and gang violence, has long been a violent area. Starting in the early 1990s, a wave of murders began to carry away the women of Ciudad Juarez. Since 1993, over 1500 women in the region have been murdered, and hundreds more have disappeared, yet to be found.

Many of the women worked in maquiladoras, low-paying garment factories that cropped up along the border after NAFTA came into effect in 1994. Protests emerged both in Mexico and around the world in response to the violence, as well as the Mexican government’s lack of response to the murders.

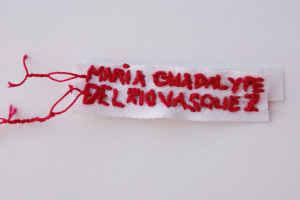

In 2005 Lise Bjorne Linnert, a Norwegian artist, began a community art project to raise awareness of femicides in Ciudad Juarez. The project, called Desconocida Unknown Ukjent, consists of hand-embroidered fabric labels, with the names of women who have been murdered in Juarez, as well as the word “disappeared” in many languages. Over 4,500 people have made 6,200 labels as part of the project. Linnert has organized workshops all over the world where people gather to stitch their contributions. They embroider one label with the name of a woman who has been murdered and one label with the word “disappeared” in their native language. The piece has been exhibited throughout Europe and the U.S.

Linnert states “To stitch the murdered woman’s name on a small piece of cloth is a physical act, time consuming, repetitious; an intimate experience. It is an act of care, in remembrance and of protest. The embroiderer brings back an identity to each name, through the trace of handwriting, stitches, and colors.” The practice of embroidering also links the project to the work many women in Ciudad Juarez do in the maquiladoras. Seeing thousands of names displayed on a wall is a powerful message about how many people have been killed.

Similarly, the Madres de Plaza de Mayo, a group of women in Argentina whose children had been “disappeared” for political reasons during the Dirty War in the 1970’s, embroidered the names of their children on headscarves and wore them while protesting. The names served as a visual reminder of these victims and an act to show that they would not be easily forgotten. While this was a small part of the Madres’ protest, the headscarves they wore became a symbol of resistance against the junta. White headscarves are now painted on the Plaza de Mayo, where the Madres still demonstrate every Thursday.

Whatever the cause, people use the tools available to them and the skills they have, be it organizing, public speaking or needlework. These two heartbreaking projects show that craft can be an act both of memory and protest.