They’re back! If you’ve attended a Baltimore Community Association meeting this month, you’ve seen them: armed with letters, announcements, and news from the state’s capitol, legislators have finished a three-month session in Annapolis and returned to the city. As they make the rounds and reconnect with constituents, there is a lot of good news to discuss. While there was much impressive work accomplished, many housing advocates hung their heads at the news that one important piece of legislation had failed — again.

The HOME Act, had it survived in Annapolis, would have required landlords to accept any kind of legal income as a rent payment. Understandably, this would have been good news for people who are experiencing homelessness but hold a Section 8 Voucher. The voucher program is a federal plan that allows tenants to pay 30 percent of their income and provides subsidies to cover the rest of the rent. Despite the ghastly-long waiting list for vouchers, the theory behind the program is that a voucher holder can choose where to live rather than residing in a particular low-income building or neighborhood. This sounds good in theory, but obtaining one does not necessarily lead to housing because many property owners can legally refuse to house tenants who intend to pay with a voucher. (Income discrimination also affects people who use Social Security or pension programs to pay their rent, so the HOME Act could have created increased housing security for many people).

By not passing the HOME Act, this behavior will continue in Baltimore City. Missteps like this one place Baltimore behind other cities in the race to end homelessness. Eleven states and 30 cities have already passed laws prohibiting income discrimination, including Philadelphia, New York City, Chicago, Philadelphia and Boston. If each of these cities is able to allow their citizens equal housing choice, why does Baltimore allow landlords to cater specifically to wealthier tenants?

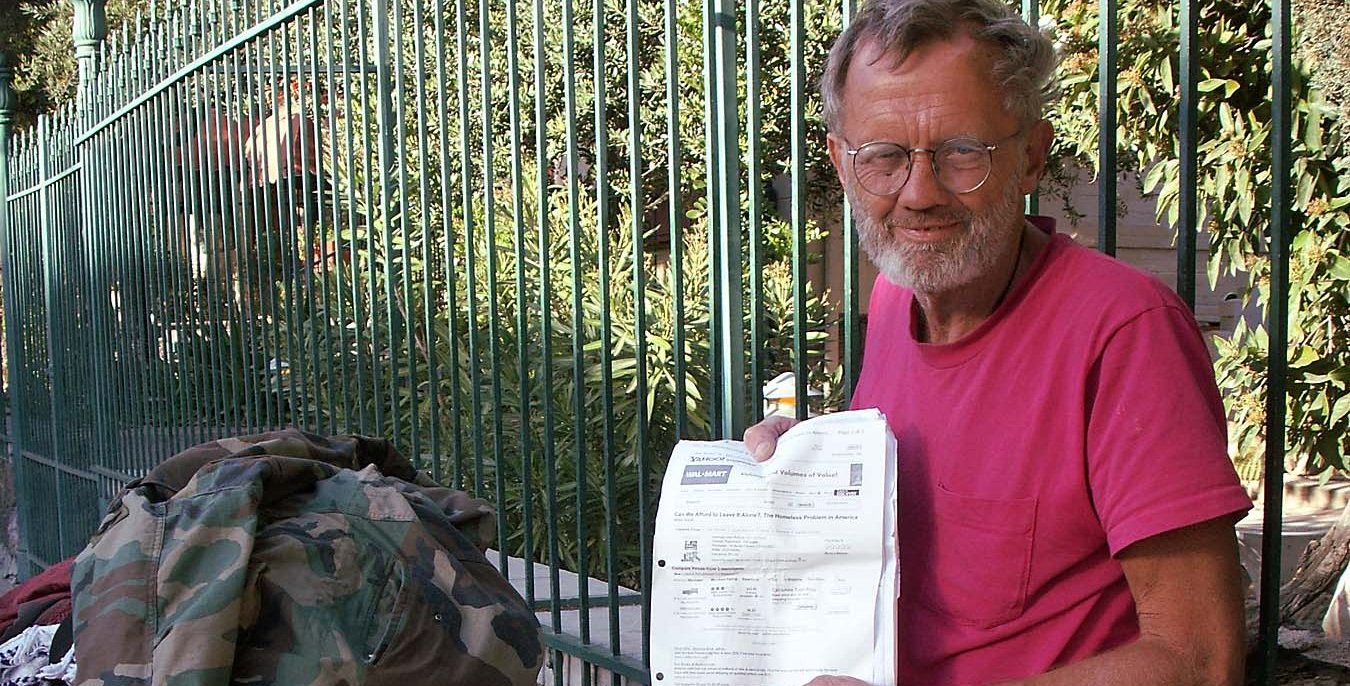

You can probably guess the answer. Fear and stigma surround homelessness, even in cities that have pledged to end it. There might be abstract support to end homelessness, but it becomes dicey when a formally homeless person is about to become your neighbor. It seems people are much more comfortable donating a dollar from inside a car than passing a low-income person in the hallway of their building. This “Not In My Backyard” mentality deters landlords from accepting Section 8 voucher holders, for fear it might upset other tenants. In reality, low-income housing has been shown not to decrease property values.

Recently, speculation surrounding sequestration suggest that Housing and Urban Development (HUD) budget cuts could actually lead to some current Section 8 tenants having their voucher revoked. In New Orleans, 700,000 recently awarded vouchers were revoked last month. It is unknown which cities will be forced to follow suit.

Baltimore should make every effort to preserve the Section 8 vouchers that have allowed low-income individuals safe and affordable housing. It is unacceptable to reverse someone’s path to housing stability. Even more crucial is a system to provide a voucher system that actually works. By working with HUD, federal policy makers, and local landlords to reduce stigma, income discrimination, and evictions, Baltimore could pull ahead in the race to end homelessness.

Perhaps next year Baltimore will be able to catch up to other cities. Until the next legislative session, income discrimination presents a significant barrier to housing, one that will slow Baltimore in its plans to end homelessness.