This week, The Baltimore Sun‘s education reporter, Erica Green, ran a story on a controversial Baltimore City Public Schools incentive program: teachers and principals are eligible for monetary rewards up to $9,500 for successfully reducing suspension rates.

Great, right? Educators can be compensated for reducing suspensions: improving school culture and decreasing disciplinary issues to keep kids in school and safe environments.

Oh, logical fallacies are so sneaky!

Logical fallacy: A reduced number of suspensions are necessarily the result of improved school culture and/or a decrease in serious misbehavior.

Likely reality: A reduced number of suspensions are the result of assigning fewer suspensions.

If Destiny and Jaqueline get into a physical fight in class, the suggested disciplinary action in the Code of Conduct is a suspension, but the actual disciplinary action comes down to administrative discretion. If the principal is eligible for a monetary reward for reducing the number of suspensions, on which side of the disciplinary action spectrum do you suppose that discretion will fall? It doesn’t take a doctorate in behavioral psychology to imagine the negative consequences of this policy.

Unfortunately, the attention to the flaws of this initiative obscures the crux of the matter: suspensions don’t work. Suspensions have almost nothing to do with school and everything to do with home and parenting.

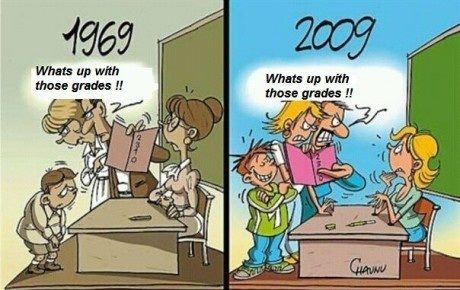

In 13 years of rigid Catholic schooling – where you could get detention for the wrong-colored socks, being one minute late, or wearing a flagrant hair accessory – I never got a single detention. Why? Well, because I was a goody-goody. But ALSO, because I did not want to even fathom the sort of wrath I would incur from my parents for receiving disciplinary action. Because I was terrified of even a single indiscretion on my “permanent record,” which I believed was very important because my parents told me so since forever. Because I knew the disciplinary action I received from school would pale in comparison to whatever my father deemed a suitable punishment. I did not worry about school infractions. I worried about what my father would say when he found out. I still shudder to imagine.

So what happens if this sort of disciplinary support doesn’t follow through at home? Nearly all of the punishing effect of detentions and suspensions are predicated on parents reinforcing the seriousness, legitimacy, and severity of these consequences at home.

In reality, many of my students viewed suspensions as a mental health day: a day of video games, Cocoa-Puffs, and Facebook. At worst, they were bored. At best – vaaaaacation!

As a teacher, I had many students with incredibly supportive parents – we chatted frequently on the phone, via email, and at conferences. They checked homework, helped with studying, and monitored grades. Not so coincidentally, these students were never in danger of being suspended.

For fairly obvious (yet complex) reasons, it is the students who do not receive adequate support and attention at home who are usually the repeat offenders for misbehavior, violent conduct, and truancy. Suspensions won’t work, because the lynchpin of the punishment is missing. Unfortunately, sending a message that extreme or violent misbehavior will be ignored or downplayed is a recipe for school chaos – that message travels fast.

What to do? These students do need some form of disciplinary action to send a clear message that certain behaviors will not be tolerated. However, they are also likely in desperate need of additional support services. Unless you have an intensely Hobbesian view of human nature, it’s fair to say that students don’t generally go around cursing, punching, and threatening people without an underlying cause.

Without digging deeper to unearth and address the root causes of the misbehavior, those students (and their schools) will be caught in a vicious cycle of crime and punishment. Maybe they need therapy and counseling services, maybe they need a positive outlet for aggression (like joining a sports team), maybe they need a personal tutor… but one thing’s for sure: a mental health day won’t fix the problem, and neither will sending them back to class.