Let me start with a disclaimer. I shop local and I believe more people should ditch the big box retailers to support the independent local businesses in their community. I believe in buying local not only because it has a greater positive impact on the economy but because it’s a better experience. I love the used book owner who saves books on the circus for me because he knows I love to find rare books on that topic for gifts for my father. I love one business owner who grabbed me out of the street to sample the latest beer he got in. I adore the quirk, the experiences, the people that you will never find without small, locally owned, independent businesses.

With that off my chest I begin part two of my examination of the Keep Austin Weird campaign and the way Baltimore has led me to examine it with three guiding questions:

- Who gets to define weird?

- Who benefits from weird?

- How can we celebrate a weird economy?

In my last post I looked at the narrow definition of weird celebrated in the “Keep Weird” campaigns. This post will pick up on that thread to look at the effect of that definition.

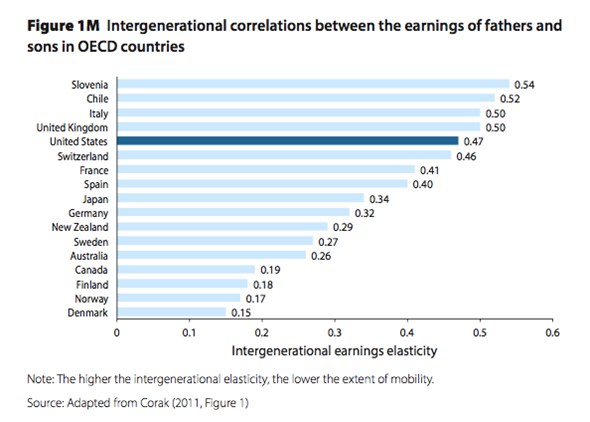

“Keep Weird” campaigns generally focus on main streets full of small boutique businesses teaming with the young eccentrics. They promote the idea that by keeping these weird places alive the city will thrive. To me, this idea sounds similar to Richard Florida’s failed promise of the creative class. Florida promoted what I’ll call the “Hipster Trickle Down Theory.” Basically in order to save a dying city, you should make it look cool so that you can attract young, college-educated, professionals to your city.

The idea that the hipsters flocking to Detroit, Philadelphia, and even our fair city of Baltimore will bring a new economic renewal has two serious flaws. The first is that like most immigrants, these new residents often form pockets of people just like them, impacting those of their kind more than the city’s natives. This influx generally results in a new suburb, only this time it is in the city limits.

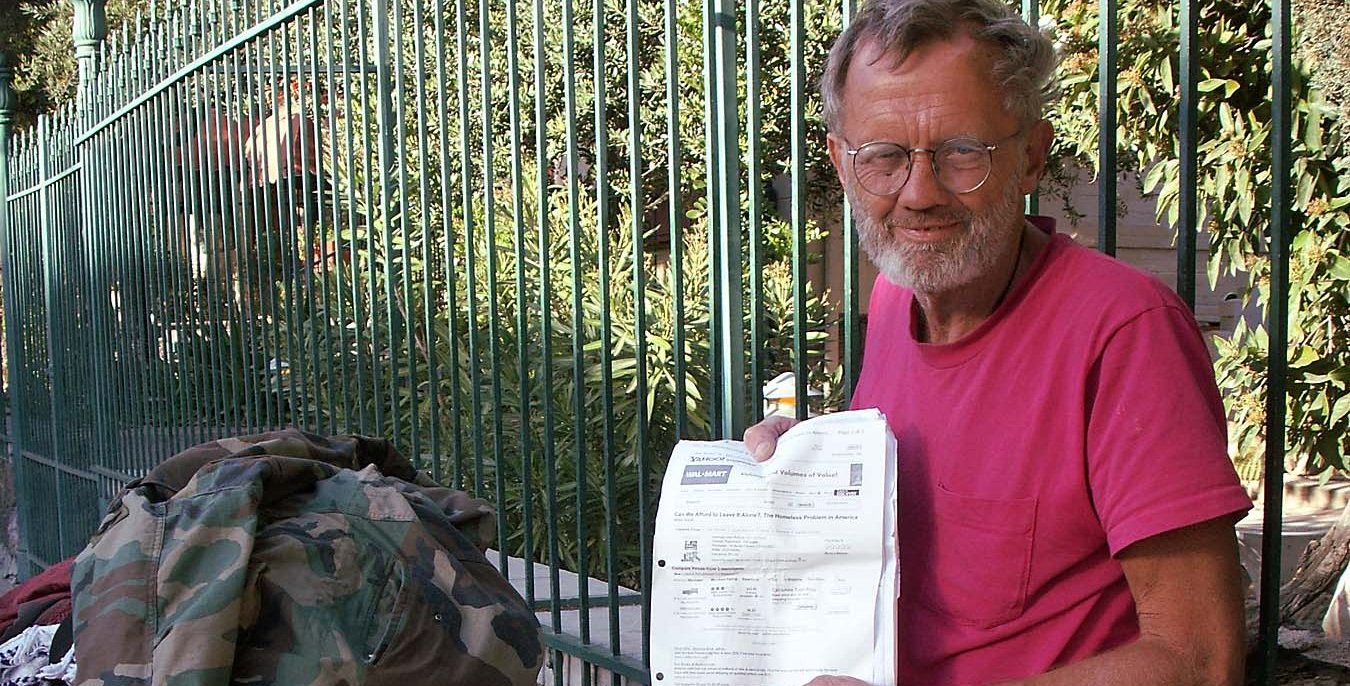

Again, it is this narrow definition of weird that is the downfall of this campaign. “Keep Weird” campaigns often do not recognize wide array of restaurants, stores, and other local businesses found in non-white areas. This specific variety of weird excludes a large part of the urban population. I think it is not a coincidence that the two largest “Weird” campaigns reside in cities with smaller African American populations than the national average. Austin comes in at 8.8 percent and Portland at 6 percent compared to a national average of 12.8%. Instead of being the symbol of inclusivity they claim to be, these campaigns generally celebrate an exclusive vision of what it means to be “Weird.” It is no surprise then that their economic benefits often fail to “trickle down” to the rest of the city.

The second flaw is the economic potential of the creative class and the small businesses they adore currently are not able to replace the powerhouses of industry that came before. While these small local businesses are important (see disclaimer above) they generally represent a small portion of the overall economic ecosystem. Currently what are really keeping those places weird are the businesses that pay people enough to patronize local businesses. Look at any rust belt town and you’ll see that when your industry dies, your local businesses tend to die with it.

Just because a business is local doesn’t mean it has what it takes to succeed. I think we need to stop encouraging people to pay a premium to patronize poor business models. What we should really focus on is how we can provide training, advice, and resources for business owners so that they can compete. One of the reported successes of the Keep Austin Weird campaign was that it stopped a Borders from opening by a local record and book store. I’m about to say what could be interpreted as a terrible capitalist-pig Scroogian statement here (see disclaimer above): if Keep Austin Weird was so wildly successful wouldn’t the local record and bookstore be able to compete against Borders since loyal Austin residents would obviously chose the local store over the corporate entity? If we want local businesses to succeed, I think we need to start talking about why local stores can’t compete and how we can help them beat out the competition.

The businesses on Main Street will not replace the jobs at the steel mill anytime soon. We need a grander vision of the new economy and I think we need to expand from simply “buy local” to growing sustainable and people-friendly local businesses. There are some local markets that businesses can take advantage of. Take Evergreen Cooperative in Cleveland which puts people back to work laundering for the city’s remaining economic powerhouses: the hospitals and universities. However, if we are seeking to beat the corporate behemoths, Austin, Portland, or Baltimore can’t do it alone. We need local businesses that are going to employ more than mom and pop and oftentimes that means selling beyond our city borders. To avoid being hypocritical (although I know hipsters love that state of being), that also means we also need to buy beyond our borders. There’s nothing wrong with this. Given the quality of Maryland wine, I want things produced outside of my community and my guess is you do too.

So I return to the beginning. How do we keep the weird shopkeepers I love in business, celebrate weird beyond Main Street, and strengthen our weird economy? Well folks, tune in next time for my third and final installment that offers a vision for a better way to celebrate weird in our cities.