I began thinking about the #SaveBmore idea in a really clichéd manner: “We need more love!” I wanted to write, before sensing all of your eyes roll collectively. Snoop Pearson’s Instagram account almost inspired me to compose a diatribe about respect, as 80 percent of her posted photographs raise middle fingers to the camera. That failed too, as did crime, homelessness, and taxes. These were failures because all my preliminary ideas blamed someone else. I found I was projecting blame, rather than taking ownership of it. Blaming guns or the economy or the actions of the police didn’t make me part of the solution, it simply made me point fingers at the perceived wrongdoings of others. In order to #SaveBmore, I would have to take on part of the responsibility.

My lightbulb moment came when I questioned not necessarily what I can do, but whether or not I actually do it — that’s when I realized the answer to saving Baltimore is all about power.

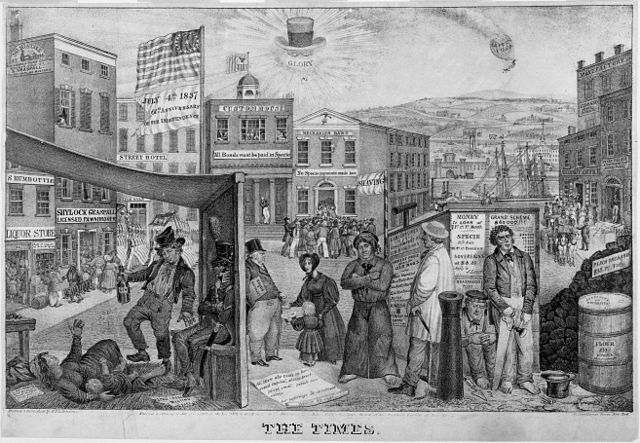

Power is a supremely complex concept. Fueled by our ability to relate to others, build our credibility, speak the right words, and play the right cards at the right time, it is the key to getting what we want, and to guiding others to act the way we feel will create a better future. Where I see the great problem in Baltimore is that power is often abused, misdirected, or left to rot — untouched and unused. As I find my professional self in rooms with influential individuals, I often think about the power they have and the power they’ve used. Some seem to use their power for good, whether that translates into public speaking, creating things that are beneficial to others, or hiring that kid who has never held a job before. Others have power through money, and donate graciously, using dollar bills and signed checks to guide their influence in what they believe are areas of promise.

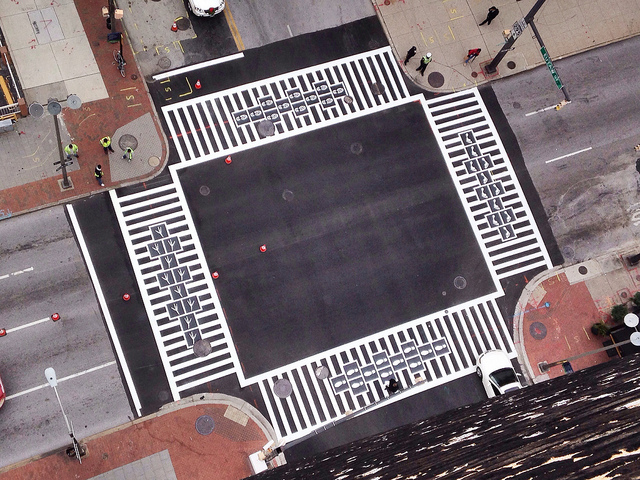

And yet there are also many who hoard their power, perhaps believing that taking no action makes them more desirable, or makes them seem more powerful to onlookers. Abuse, misuse, and the refusal to use power is the reason we can’t get ahead in this town. At a recent meeting where several individuals pushed for increased public transit shelters around the harbor, the request was met with a resounding no — ‘case closed.’ What struck me was not the no itself so much as the refusal to even justify the denial, an attitude that’s far too common in our fair city. Somewhere, I thought, there’s an individual with the power to make lots of people happier and more comfortable, and they refuse to do so. That routine refusal by those in power — whether to create more bike lanes, question arrest policies, or approve a shelter — is what keeps Baltimore from reaching its greatest potential.

But I said I wasn’t here to blame others. The fact is that we all have power that we refuse to exercise — whether out of fear, ignorance or inertia. We can heal, create, speak up, and — where necessary — act out. A few of us even have the ability to exercise power through a signature or an endorsement. I believe Baltimore will be saved not simply through the recognition of our own power, but the courage to exercise that power. Every moment we don’t is another time we shirk our responsibility — to use the power to create change that we are all fortunate enough to hold.