A bad credit history was the only thing keeping the 19-year old James Ward from attending Howard. Ward had been homeless for most of high school but had worked hard and managed to get into a large university. However his mother’s bad credit made him unable to get student loans that would financially enable him to go. So, showing a spark on ingenuity, he found a different way to fund his college education. Ward started a campaign called “Homeless to Howard.” Using only a Tumblr blog and Paypal account he was able to launch an online campaign that helped him raise $12,000, enough for his first year of college.

Access to credit is one of the many “poverty traps” that exist today, mechanisms that create the cycle of poverty and limit inter-generational mobility. Having no credit is just as bad as having bad credit and it is hard to start credit if no-one in your family has good credit. Today, credit can affect your access to everything from an apartment, utilities, cell phones, and as in the example above student loans. Not having credit excludes you from accessing affordable services and loans that allow you to work your way out of poverty.

Photo from University of Denver

Luckily new ways of financing are starting to evolve. In the developing world where a student loan system doesn’t exist, microloan systems are coming in to fill the void. Vittana allows people to make $25 loans to students across the world to pay for their education. Graduates make on average 2.8 times more than before and thus there is a 99.8% repayment rate. Two years ago, Kiva, a well known global microlender announced it would start providing small, no-interest loans for student’s education in countries across the globe. Kiva got in the business because they recognize that financing student loans are not appealing to most lending institutions interested only in return. Students have no collateral, require long terms and grace periods, and often have no prior credit history. Making student loans is more appealing to a organization like Kiva where investors are more focused on making social change than getting a financial return.

Lumni, which now operates in the United States asks investors to think of students like start up companies. Through Lumni, investors fund student’s education and those students must promise to give investors back a percentage of the income they make for their first ten years out of college. A deal like Lumni means investors care not only about whether or not the student can pay back the student loans, but how successful they become. They become stakeholders in the student’s future and will do more to make sure they succeed.

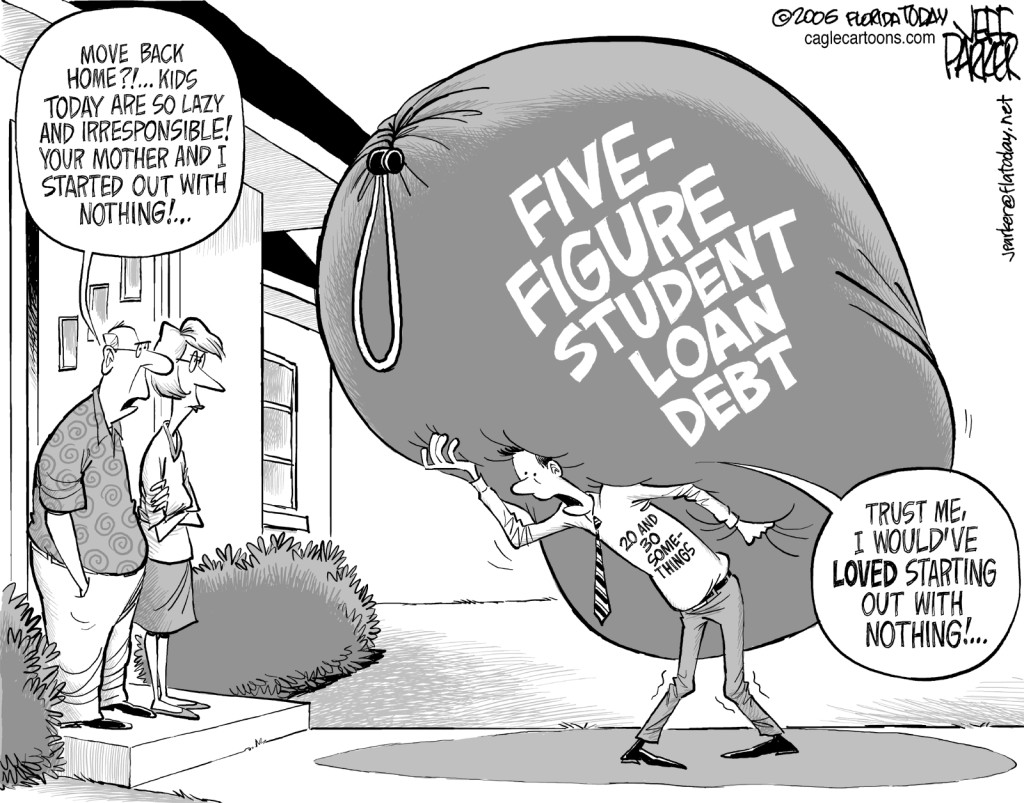

Cartoon by Jeff Parker

American students today leave college with massive amounts of student debts. My generation has seen first hand what happens when you come out of college with loan repayments to make and no good job in site. When faced with a choice of taking a low paying entry-level job at a company that will be an in to your career and a slightly higher paying job at Starbucks, many graduates must chose the latter so that they can start making repayments. Furthermore during their first years, they often shovel so much back into paying off their student loans that they don’t save anything which can cause further financial instability and could result in more debt if any other emergency or need arises.

In contrast a new system, in which loan makers are invested not only in getting a return, but also in student success could not only increase access to funding for education for students like James Ward, but create a system that ensures better success and financial stability for our college graduates. Instead of investing in immediate returns, these social enterprises invest in the future. This allows students to have a grace period to make decisions that will set them up for further success in the long run. It’s a triple bottom line approach that could ultimately lead to larger profits both monetarily and socially for all involved.