(Photo by tcp909.)

Let’s talk about something near and dear to my heart. Hot dogs. Yep, you know you love ‘em. Whether it be a homemade weiner with kraut from Binkert’s or a dirty water dog sporting mustard and neon-green relish, hot dogs rank pretty high on my favorites list. So it really struck me when I heard Candy Chang talk about one of her many design for change projects, a Street Vendor Guide for New York City’s ubiquitous food cart vendors. She spoke last Thursday as part of the Mixed Media Lecture series hosted by the Center for Art Education and the MICA Graphic Design department.

Chang describes herself as an artist who wants to make cities more emotional. She is a TED Senior Fellow, a Tulane Urban Innovation Fellow, a World Economic Forum Young Global Leader, and was named a “Live Your Best Life” Local Hero by Oprah Magazine. By combining public art with civic engagement and personal well-being, she has been recognized for exploring new strategies for the design of our cities in order to live our best lives. More of her biography can be found here.

We choose what consumes our hearts. The world becomes more rewarding when you look beyond what you’re searching for. —Candy Chang

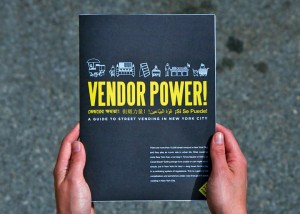

Chang worked with Rosten Woo and John Mangin of the Center for Urban Pedagogy (CUP) and Sean Basinski of The Street Vendor Project to make the Street Vendor Guide an accessible and understandable presentation of important regulations. They found that many vendors were receiving fines of up to $1,000 for small violations that could easily be avoided. Taking a look at the old regulation documents, however, one could easily see how the information was getting lost in translation, often quite literally. Chang designed a new vendor guide that depicts the safety rules and street regulations in easy-to-understand illustrations accompanied by text in Bengali, Arabic, Chinese, English and Spanish. It also includes policy reform recommendations and personal vendor stories. Guides were distributed for free to thousands of street vendors and are available as a download from the CUP’s Making Policy Public site.

This is just one example of how Chang’s work has shifted a microcosm. Her other work is equally inspiring, crossing the intersections of public art and urban planning, design and communication. One of her more recent projects is Neighborland, an online tool about real places that stemmed from her I Wish This Was public art installations. It promotes community discussion about ways to improve common spaces and connects like-minded citizens with an emphasis on pooling resources. The website encourages residents to speak up about what they want to see change in their city. Prominent street signage encouraged people to also text their ideas to the site, allowing conversations and grass-roots efforts to oscillate between the screen and real world. This unique project is an example of how the gap between the online world and reality can be bridged. I think future efforts to further explore the possibilities of this connection between technology and community will become cutting edge innovations in social change.

So I was describing this post with some enthusiasm to a friend, and explaining the street vendor project as an example of social design. “Cool,” said the friend, “who paid for it?” That struck me as a very good question. I’m curious too how this project was funded, and, more broadly, how social design projects are generally funded and a discussion of how they should be. The economics of social design.