We’ve all heard it. Many of us have said it. It’s a plea, a prayer – uttered so often it’s damn near a mantra:

“We’re not just The Wire.”

Baltimore wants nothing more than to be seen as something other than a byword for crime and decay, for poverty and violence. We’re not just the wasteland made notorious by David Simon’s landmark series, occupied by drugslingers and sociopathic murderers and sicklied over with impenetrable despair. That’s just the image that’s been conjured up in the public imagination, we say. We’re sick of people’s eyes growing wide in horror when they hear what city we live in, the inevitable questions … “Is it like that? Is it just like The Wire?”

In the past few weeks here at ChangeEngine, we’ve been debating what might “save” Baltimore from a present and a future where so many are condemned to a shadow existence and forced to the margins by poverty and inequality. And yet it seems like what Baltimore wants to be saved from most of all is itself, to be delivered from the stain on our reputation, the shame of The Wire; to shunt those things that cast an ill light on our collective existence back into the shadows.

But that shame, left unchecked, will destroy us. If we truly want to save Baltimore, to save ourselves from the perpetual instability of illusory wealth and the criminal waste of lost promise; if we truly want to fulfill Dr. King’s vision of a “beloved community” rather than languish in the spiritual poverty of a divided society, we must not be ashamed. We must not shy away from what The Wire represents and the heavy burden it lays at our door … because we are The Wire and we need to own it.

What we’re saying when we deny The Wire is that we’re not just ‘those’ neighborhoods, not just a city of poor black people embroiled in the drug war. In trying to sweep those people and places from our consciousness, we not only caricature what The Wire actually depicted but fail to heed its prophetic call. As David Simon said:

“[T]hat’s what The Wire was about … people who were worth less and who were no longer necessary, as maybe 10 or 15% of my country is no longer necessary to the operation of the economy. It was about them trying to solve … an existential crisis. In their irrelevance, their economic irrelevance, they were nonetheless still on the ground occupying this place called Baltimore and they were going to have to endure somehow.”

When we say we’re not The Wire we’re saying we should be like one America, and forget the other. And that we can only succeed if these people, this other Baltimore, disappears. But that’s impossible, it’s unsustainable; it will undermine the very future we hope to create by ignoring the things that horrify and embarrass us. The ONLY way we can make Baltimore not just about The Wire is by embracing the story it tells about us.

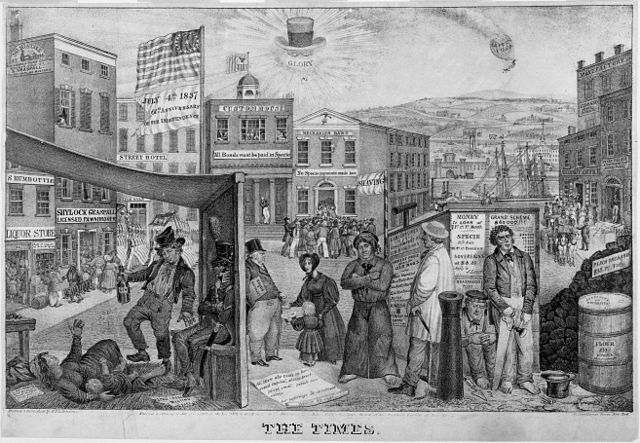

“See, back in middle school and all, I used to love them myths,” says Omar, the predatory gunslinger who roams Baltimore’s streets like a swaggering pirate as he schools a sheriff’s deputy about the Greek god of war. So complete a work is The Wire, so vivid and eternally real are the likes of Omar, Stringer and Bubbles that these offending shadows have become our mythology, our epic.

Whether it’s Omar resplendent in a shimmering teal dressing gown, scowling at the terrified ‘puppies’ who fling their stashes his way on his early morning hunt for Honey Nut Cheerios; Clay Davis’s sheeeeeet! stretching on to the last syllable of recorded time; a forensic epiphany derived entirely from a dialogue of f-bombs; the death of Wallace, of Bodie and Sherrod, of Prop Joe; the fall of the Barksdales, Dukie’s descent or Cutty’s redemption – these moments confer an identity that’s deeply ours, as iconic and intrinsic as Poe’s mournful features and gutter requiem.

This is our story, an epic of the American post-industrial city struggling for existence and meaning where all sustaining truths and certainties have been annihilated. It has the power to unify our consciousness and to rouse us to collective action. The Wire didn’t focus on the “bad side” of Baltimore; it cast a glaring light on what was wrong with America. Its creators offered us a study of dysfunction and neglect – a diagnosis, a pessimistic prognosis, and no real hope of a cure. That part is up to us.

And yet the cures we’re presented with are largely exercises in denial – efforts to tell a different story rather than confronting and changing the one we have. We are told to ‘Believe’ in Baltimore, then beggar belief by proclaiming ourselves ‘The Greatest City in America.’ We swear up and down that we’re not The Wire, as though that wire is live and we dare not touch it.

In the standard gospel, salvation comes through expanding the ‘white corridor’ that runs along 83, pushing out the ‘bad Baltimore.’ The Grand Prix, the creative class, a shiny new development downtown – these are the pet miracles of urban renewal evangelism. But without justice, they can only be a mirage. Just as civil rights activists were willing to be beaten and bloodied because they knew that no-one is free unless all of us are free, not one of us can say he is truly wealthy as long as any of us is poor. As long as we’re erecting monuments to distraction, condo towers with a stunning view but no vision, we’ll be blind. No sustainable salvation can come of growing that privileged bubble. We’ll fool ourselves into complacency, into thinking we can ignore The Wire, and the bubble will burst.

Saving Baltimore requires a shift in thinking, a hard confrontation. It requires ambition and audacity – the kind that causes a person to get up every day and try to keep children from dying on the streets, to battle slumlords who profit from blight and misery, or fight to keep the prison industrial complex from throttling whole communities. We would do well to pay tribute and attention to those on the front lines of social change, who wrestle with the darkness, who suffer a thousand everyday defeats and win a thousand everyday victories in the struggle to make a better world.

Like them, we must grapple with the darkness. Most urgently, we must fight to end the drug war. As The Wire makes so vividly clear, the war on drugs has become a war on the urban underclass, a war on the most vulnerable and powerless. Each drug arrest in this city costs us at least $10,000. Statewide we spend hundreds of millions of dollars to incarcerate non-violent drug offenders, 90 percent of them African-American. This despite clear evidence that white and black people use and sell drugs at roughly the same rate.

In the starkest of terms, black (and poor) people are being arrested and incarcerated, their lives ruined, for something everyone does. And that is the greater cost. This war destroys families, robs children of their parents and leaves them destitute, cripples chances for employment and advancement, and causes young people to be murdered in the streets as they scuffle over turf in a society that gives them nowhere to call their own.

We can change that story. Think what all the resources squandered on this folly could do if devoted to social change, what dynamism could be unleashed. Think of what it would mean to reclaim all the talent and energy lost to the criminal justice system and to the miasma of distrust and despair that crushes and humiliates the spirit and leaves so many feeling that the game is rigged against them.

This is about more than just one policy. Just as we condemn an addict to the clawing, scraping chaos of the criminal underworld when we force him into the shadows, so too do we deny ourselves a brighter future and invite in all the ills we run from by denying what The Wire says about us. Baltimore could be the one city in America that truly confronts the issue of its underclass and the ravages of exclusion rather than pretending it’s not there and brutalizing it when it rears its head. We must resolve that we don’t want to run from The Wire, but rather change the system that generates those conditions.

The engine of salvation is not in our stars but in ourselves. We need a Manhattan Project for transformation, a space race for social change. Let’s work to provide the greatest rewards to those whose efforts most benefit the least well off. Let’s energize social change makers to move to Baltimore and cultivate those already here. And let’s start treating them like rock stars, not martyred idealists.

Baltimore doesn’t have a PR problem; we have a poverty problem. We don’t need a better image; we need a better way. We need to celebrate and attract those who want to make a difference, not engage in a desperate charade to prove we’re just the same. So Just Say Yes – we ARE the Wire. Only then can we change the story. Only then can we start building a city of which we’ll never be ashamed, a place where every one of us is truly cherished.